Essay: Arrested Development

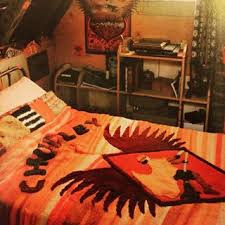

Early in Harry

Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, Harry visits the Weasley house for the

first time. Ron’s room is covered in paraphernalia from his favorite Quidditch

team, the Chudley Cannons, a name that includes a weapon. Ron is marked as a

future warrior because of his proficiency at chess, but his insecurity is also

showing due to his allegiance to the Cannons. This team is ninth in a league of

thirteen teams, and their motto is, “Let’s all just keep our fingers crossed

and hope for the best.”

Quidditch and

games are frequently key to this book and, as in the first book, games again segue

into battles. However, the most prominent “game” this time is that the plot is

shaped by one of the most famous fairy tales of all time: “Little Red Riding

Hood”, which I’ll cover extensively in the next blog post. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 13: Deus ex Machina.)

There is also a fairy tale in Deathly

Hallows called “The Three Brothers”, by the wizard writer Beedle the Bard.

This tale is instructive to Harry, and in the final book, we see yet again that

Voldemort disregards fairy tales, children, childlike beings like house-elves,

and children’s toys and games to his peril. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 1:The Kids’ Table.)

Looking at Grimm’s

version of “Little Red Riding Hood” beside Rowling’s, plus some other works for

young people, we can see that Voldemort has something in common with many fairy

tale villains: he tries to make more than one child grow up too soon because he doesn’t value

childhood or the natural life-cycle, which of course eventually leads to death,

something he also tries to avoid at all costs. When childhood and its trappings

are not valued the next logical step by the enemies of childhood, toys, games

and imagination is to have a child skip it and go directly to adulthood—or to

just skip over the rest of that child’s life by killing the child. Arresting a

child’s development and keeping them as a child forever is another type of

death; they are frozen as children for all time, just as someone is who dies in

childhood.

Many readers have

picked up on numerous sexual overtones in the climax (no pun intended) of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets:

there’s a descent into a forbidden chamber through a long, slimy tunnel

accessed through a girls’ bathroom. There’s the basilisk—the king of snakes—moving

through this tunnel. (Here I believe JK Rowling is making a joke that is

absolutely intended for her adult audience, even as it flew over the heads of children

reading the books.) Only Harry,

Ginny’s future husband, can enter the chamber to rescue her, while her brother Ron

and her teacher, Gilderoy Lockhart, are trapped on the other side of a fall of

rock. For either of them to enter the Chamber to retrieve her would be symbolic

incest—in one case brother-sister incest and in the other adult-child incest. This

is also why Ron and Hermione enter the Chamber together in the seventh book, and soon after, they share their

first kiss.

Rowling is not

suggesting that Harry and Ginny actually have or should have sex, even

symbolically, in the Chamber. They’re saved

from the chamber, a symbol of sexuality to which they’re subjected too soon because Tom Riddle has been

attempting to symbolically mature them too early, entering a chamber that is

womb-like and full of sexual symbolism, but is designed to bring death.

Skipping childhood

and going directly to adulthood is, in many stories, a kind of death. In Ray

Bradbury’s Something Wicked this Way

Comes and in Cornelia Funke’s The

Thief Lord, a boy rides an enchanted carousel, but afterward he disembarks

the carousel as an adult, having skipped the rest of childhood and adolescence.

This is treated as a tragedy. Other stories in which children have their

childhoods taken from them because they must behave as adults while still

children, supporting themselves or taking care of younger children, such as

Wendy’s character in JM Barrie’s Peter

Pan, are also considered distortions of childhood, even though our modern

Western conception of “childhood” is less than two centuries old.

In these stories,

skipping the normal maturation process is no better than remaining a child

forever, like Peter Pan; the natural order has been violated. The “Lost Boys” in

Peter Pan are not just “lost” because

they’re in Neverland. They’re not permitted to grow and mature, which is analogous

to their having died as children. This is why it’s appropriate that Nancy

Farmer uses the term “Lost Boys” to label child-clones in her book The House of the Scorpion. Farmer’s

“Lost Boys” will eventually be used to provide organs to the adults from whom

they were cloned. This is also why it’s also appropriate that the film The Lost Boys is about teenagers who’ve

become vampires. Their development is also permanently arrested and they will

never truly grow up.

Children who die

are frozen in memory as children for all time; they never age. The Petrifaction

of the basilisk victims in Chamber of

Secrets is a similarly unnatural fate. JM Barrie wrote, “All children,

except one, grow up.” But perhaps that should be—all children except one, and

except any children who are killed or Petrified by a Basilisk.

It’s worth noting

that in Chamber of Secrets, no living

human adults are Petrified. Instead, the basilisk has made some Hogwarts

students into Peter Pans or Lost Boys, children frozen as children. Because of

this, it’s also appropriate that the ghost of Nearly-Headless Nick is affected.

He’s frozen as he was when he died because he’s obsessed with the way that he

died; this is why he’s a ghost. He’s

a metaphorical permanent child who can never mature. This is also true of

Moaning Myrtle, who was killed by the basilisk, so she remains a child for all

time, perpetually haunting the girls’ toilets, a location on the symbolic cusp

of maturity. Her name also refers to a plant that’s included in bridal bouquets

for “memory”, which is all Myrtle can do now: remember.

In a June 2003

interview with Jeremy Paxman, JK Rowling called the idea of making Harry a

Peter Pan who doesn’t mature but remains innocent of the appeal of girls,

“sinister”.

Jane Langton is

similarly disapproving of children frozen in one form too soon and not

permitted to mature naturally. In Langton’s The

Diamond in the Window, Eleanor and Eddy Hall are orphans who have mystical

adventures in Concord, Massachusetts, where they live with their aunt and

uncle, the siblings Lily and Fred Hall.

In one of their

mystical adventures, taking place in a dream that is all too real, Eddy and

Eleanor are very small, walking across the top of a dresser with angled mirrors

repeating their images. They enter a mirror and discover that their reflections

are not the same thing over and over but images of themselves that are growing

and aging. These are their potential futures, people they haven’t yet become.

They must carefully choose who they want to be to progress safely through the

mirror-maze. There are many more possibilities than what Ron sees in the Mirror

of Erised. Langton makes it clear that these children don’t yet know what their

hearts’ desires are. They haven’t yet been “frozen” into these adults, there’s

only potential, and this is still technically a game, not a real battle, which

their game will evolve into later, though every magical adventure they go on

has its dangers.

In Langton’s

second book about the Halls, The Swing in

the Summerhouse, Eddy and Eleanor’s new uncle-by-marriage, who was

responsible for the adventures in the previous book, creates more magical

adventures for his niece and nephew. He’s built a six-sided gazebo, or summerhouse,

but doesn’t have time to finish it before taking a trip. Instead he boards up

one of the six archways and paints KEEP OUT in large capital letters on these

boards, though the children can still come and go through the other five openings.

He would prefer that they not go through this one without his guidance, and

they promise to abide by his wishes.

When he and his

wife, the children’s Aunt Lily, must leave the children in care of her brother

Fred, Eddy, who’s very handy, notices that a swing that can turn in any

direction would be a good addition to the summerhouse and he installs one. He

and his sister Eleanor soon discover that the summerhouse is magical and

somewhat dangerous when their rambunctious friend Oliver hops on the swing,

laughs at the KEEP OUT sign, and breaks through the boards, swinging out

through that archway and disappearing. The game of playing on a swing has

quickly turned dangerous, and they now understand why their uncle boarded up

that opening.

Because they

promised not to go through that archway, Eddy and Eleanor seek Oliver by

swinging through the other openings. After they’ve gone on adventures through

four archways—which take them to different worlds—adventures that all begin as

games and become far more dangerous, they find that they can’t go through the

fifth one—just as there was that one door Harry couldn’t go through in the

Department of Mysteries. There’s only one opening left: they know that they

have no choice but to enter the forbidden archway.

Four of the six

openings have legends above them that reflect their adventures. The one they

can’t go through because the swing won’t turn that way is labeled YOUR HEART’S

DESIRE. Both Langton and Rowling know how tempting this sounds. The forbidden archway,

however, is labeled GROW UP NOW.

Along with Oliver,

two other new characters are introduced in this book: Georgie Dorian, a

four-year-old who desperately wants to learn to read, and her mother, a widow who

Uncle Freddy has fallen in love with. After going on an adventure with Eddy and

Eleanor through another archway, Georgie is aware of the summerhouse’s magic

and knows what the labels on the openings say because Eddy and Eleanor read

them to her and she memorized them. Believing her reading problem would be

solved if she could GROW UP NOW, she goes through the KEEP OUT sign that Eddy

rebuilt after Oliver disappeared. She enters the forbidden chamber.

When Mrs. Dorian,

Georgie’s mother, realizes that this is where her daughter has gone, she also swings

through the archway. Eddy and Eleanor decide to follow her, despite their

promise to their uncle. Rowling is hardly the first writer to depict children

making difficult moral choices; Harry knows that promising not to look for the

Philosopher’s Stone is a moot point when Voldemort might get his hands on it. Eddy and Eleanor have

lost a friend and exhausted all other means of finding him. Now another friend

and an adult are missing. They feel they have no choice but to break their promise.

When Eddy and

Eleanor swing through the forbidden archway they find that they are still in

their town, in their garden. But it’s a very quiet version of their world and

they quickly realize that it’s not

their world. They find Oliver, Georgie and her mother, who are now stone

statues, as though Petrified by a

Basilisk.

Philip Pullman

also addresses the issue of freezing children perpetually in their

pre-adolescent state in a series of books called His Dark Materials. The three books are The Golden Compass (it was called The Northern Lights in the UK), The

Subtle Knife and The Amber Spyglass.

The heroine of the series, Lyra, lives in an alternate reality where an aspect

of humans’ souls lives outside their bodies in the form of a “daemon”. This

external manifestation of the soul is a shape-shifter before a person reaches

adolescence, morphing from a mouse to a sparrow to a moth to a bobcat in the

blink of an eye. This is similar to Eddy and Eleanor seeing their possible

futures in the images they encounter in the mirror maze. Before a child becomes

mature, their daemon is a host of possibilities. After maturation, a person’s

daemon takes on a single form that in some way captures the essence of who that

person is.

A daemon is a

non-human creature that can be a mammal, a reptile, a bird, an insect, just

about anything. The daemon’s gender is usually the opposite of the person,

though Pullman does mention, in passing, a character with a daemon of the same

gender. Pullman himself says this may or may not be indicative of a same-gender

sexual orientation or even second-sight, which implies that this character

might be Liminal. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 8: Have You Tried Not Being Liminal?)

A male character in the series speaks of his daemon as the femaleness in

himself, something he didn’t think about until she manifested as his daemon.

A daemon is nearly

always by a person’s side, and when it moves too far from its host, that host

is uncomfortable and twitchy. In Pullman’s universe, only witches and shamans

can send their daemons farther afield, to be their eyes and ears. With this device, Pullman seems to say something

similar to Rowling about the unnaturalness of splitting a body from a soul,

which is what the Dementor’s Kiss accomplishes and what Voldemort does by

dividing his soul.

At various times

in His Dark Materials adults try to

prevent children from growing up, which can be viewed both as the children

becoming sexual beings and becoming sentient, moral beings, which is to say,

they become capable of immorality. In

a misguided attempt to “save” children from the “sin” stemming from spiritual and sexual awakening, adults try to

prevent the maturation process by separating children from their daemons—their

souls. Adult survivors of this still-experimental procedure are depicted as

zombie-like, going through the motions of life, placid and obedient slaves. It

seems to have the same effect as both the Dementor’s Kiss and the Imperius Curse

in Harry Potter, except that Imperius

can be resisted.

This is

reminiscent of another part of Nancy Farmer’s The House of the Scorpion, in which people who have chips implanted

in their brains are called eejits or zombis. The chips take away their

volition and these people no longer even eat or drink unless they’re ordered to,

no matter how hungry or thirsty they are. They’re perfect servants,

unquestioning and obedient. Seven years before The House of the Scorpion, in the first His Dark Materials book, Pullman already presented the idea of the zombi being a “slave” created by

separating a person from their daemon, which is the same as their volition or soul.

Farmer, Pullman and Rowling all seem to agree about the sinister nature of

removing a person’s volition: dividing someone from their will, which seems to

be bound up in the soul, is

unnatural.

At one point in

Pullman’s story, Lyra’s mother tries to arrest her development by drugging her

daughter, who is on the cusp of adolescence, by hiding her in a cave to protect

her from people who want to kill Lyra and permanently

arrest her development. In some classic fairy tales, such as “Snow White” and “Sleeping

Beauty,” the heroine falls into an enchanted sleep or is imprisoned in a place

that makes pursuing her untenable (“Sleeping Beauty” again, due to the hedge of

thorns, and Rapunzel in her tower, which is as much a symbolic womb as the cave

where Lyra is in her drug-induced sleep).

A mother- or

father-figure is usually the one causing this unnatural state of affairs. Often,

the mother is unwilling to let the girl mature and become what amounts to a

sexual rival, and in fact, Pullman’s hero, the young Will, who falls in love

with Lyra, is a little attracted to Lyra’s mother. If a father has imprisoned

or drugged his daughter, he may be fighting a growing though subconscious

attraction to her, so he locks her away to keep her from any man, because he

cannot have her himself. This is a fairy-tale trope that Shakespeare used in The Tempest and it often leads to

marriage tests such as the fairy-tale motif of a father forcing his daughter’s

suitors to slay monsters, solve riddles, or just choose from a selection of

gold, silver and lead boxes, which again is a trope that Shakespeare used, this

time in The Merchant of Venice.

JM Barrie does not

depict Peter Pan’s state as natural or desirable. Wendy’s frustration with

Peter’s being satisfied to play at being a father while she plays at motherhood

builds and builds. She knows that she must eventually set these games aside,

return to her parents and grow up. In the end, we’re told that she has a child,

and that child grows up and has a child, and so on.

But adults

shouldn’t completely forget what it is to be a child. In The Swing in the Summerhouse, Uncle Freddy, an archetypal Wise Old

Man, like Dumbledore, goes through the forbidden archway to find those who have

gone before him and have become, in effect, Petrified. Along with Oliver,

Georgie and her mother, now Eddy and Eleanor are also solid stone. But they

still have long childhoods ahead of them, and Uncle Freddy urges them to

remember that they are children, or,

in Mrs. Dorian’s case, he reminds her how to think like a child, by playing

Hide and Seek, calling to all of them, “COME OUT, COME OUT, WHEREVER YOU ARE!”

Unlike many adults, Uncle Freddy has never stopped valuing play, games and

imagination. He’s not a child, chronologically, but he still values the

trappings of childhood, like Dumbledore. That this call also awakens Georgie’s

mother is a sign that she and Uncle Freddy are kindred spirits, and before the end

of the book he proposes to her.

In most fairy tale

cases of arrested development, usually of a girl, this is overcome with a happy

ending that includes the equivalent of marriage to her counterpart. In

Pullman’s scenario, Will, an archetypal Youth, awakens Lyra, an archetypal

Maiden, and eventually takes her to a place where they are alone and can

realize their feelings for each other. They are away from adult supervision and

the taboos against exploring physical and spiritual maturity. It seems

uncoincidental that the Youthful hero, whose name is “William” is usually

called “Will”. He is always in possession of his will, his own volition, not

surrendering it to anyone at any time, the true embodiment of a hero but also a

frightening idea to adults who wish to control a child—or anyone.

Pullman tells us

that servants nearly always have dog-daemons and are said to like orderliness,

knowing who’s in charge, and following commands. He

uses the shape-shifting daemons again to illustrate Will and Lyra’s maturation;

from now on their daemons will no longer shift and change but remain forever in

one form. Though he repeatedly mentions a taboo against touching others’

daemons and though another person’s daemon may touch your daemon, having a

lover touch your daemon is described as a cross between physical and spiritual

ecstasy. Is Pullman concerned with a physical or spiritual awakening? It seems

that the answer is both, and the same also seems to be true for JK Rowling in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.

Adapted

from the script for Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 12: Grow Up Now, Copyright 2017-2018 by Quantum Harry Productions and B.L. Purdom. See

other posts on this blog for direct links to all episodes of Quantum Harry.

Comments

Post a Comment