Essay: Red Riding Hood Goes to Hogwarts

Many readers have

(rightly) seen traces of famous myths in Chamber of Secrets, such

as Persephone and Hades, in addition to the abundant sexual symbolism in the

book. In an earlier blog post (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 3: Iron Maiden),

I compared Ginny Weasley to Persephone because they both embody the archetype

of the Maiden and Persephone’s return from Hades each spring was similar to

Ginny’s return from the Chamber, which brings her world back to life the way

that Persephone’s return each spring also reawakens the world.

However, “Little

Red Riding Hood” is the story that really pervades the book, and this positions

the second Harry Potter book at a

very important place in a Young Adult series: after this Harry is spiritually

mature and no longer needs rescuing.

As rewritten from

numerous folk-sources by Wilhelm Grimm, “Little Red Riding Hood” is a

Pentecostal tale. Pentecost is the Christian holiday that comes fifty days

after Easter; many people consider it to be the “birthday” of the Christian

church. In Acts 2:1-31, the story of Pentecost is told, when the Holy Spirit

appears as tongues of fire on the heads of Jesus’ disciples, or so the story

goes, after which they can speak in languages they previously hadn’t known.

Some biblical

scholars call this the flip side of the story of the Tower of Babel, in which

God is supposed to be upset about humans having the presumption to try to build

a tower reaching heaven, so they all suddenly start speaking in different

languages and can no longer understand each other—they sound like they are

“babbling”, in other words. In his book The

Great Code: The Bible and Literature, Northrop Frye writes that biblical

scholars say the Tower of Babel story is a tale that ‘prefigures’ the Pentecost

story, or foreshadows it, as well as flipping it—we go from an angry god

confusing humans’ speech so that they will not commit an act of hubris, to the

Holy Spirit making it possible for humans to speak the language of the Other in order to

spread the Gospel.

By the middle

ages, Pentecost was traditionally when young people in Europe were “confirmed”

and joined the church, after which they were considered adults. Wilhelm Grimm

was aware of this when he added the woodsman to “Little Red Riding Hood” as a

savior-figure, to avoid the heresy of Pelagianism—the idea that humans can be

saved from damnation without an outside agent to make up for the Original Sin

stemming from the Fall in Eden. Pelagianism is the opposite of Divine

Providence, a theological concept that was very important to Grimm.

Grimm’s religious

motivation for rewriting many old folk tales as “religious poetry” is

documented by G. Ronald Murphy in his book The

Owl, The Raven and the Dove. Murphy asserts that Grimm also rewrote “Hansel

and Gretel” to conform to this religious ideal. In early versions of that

story, the brother and sister escape from the witch who is fattening Hansel

in a cage and they return home under their own power, whereas Grimm confronts

them with “an unbridged river”, creating the necessity for them to rely upon

what Murphy calls “supernatural transport”. Murphy, a Jesuit, equates

this with God’s grace and the intercession of the Holy Spirit.

An outside agent—or

a savior—being necessary in a story to avoid blasphemy wasn’t an idea created

by Christianity. Long before Wilhelm Grimm or Christianity, Greek playwrights

used the deus ex machina in stage

dramas. The “god from the machine” (the meaning of deus ex machina) was an actor portraying a god who was lowered or

raised onto the stage by a mechanical device, bringing proclamations concerning

the characters and tying off any trailing plot threads with the wave of an

omnipotent hand.

Today the deus ex machina in any kind of writing

is considered a trite, “easy” solution, and when it’s called out it’s not

usually because a critic wants to praise the author for avoiding blasphemy. Many

critics of this device may not even know it had anything to do with blasphemy,

but if you’re going criticize this in pre-modern works it is wise to recognize

that it was originally meant to show respect. It was an embodiment of a common

belief, crossing religious lines, that humans’ salvation was in the gods’

hands, not our own. There are people who still adhere to this belief, and people

are still writing works with a deus ex

machina of some sort, quite deliberately.

The insertion of a

savior into “Little Red Riding Hood” isn’t Grimm’s only manipulation of the

story. The Charles Perrault version is a cautionary tale: the girl and her

grandmother are devoured by the wolf at the end, which is abrupt and violent.

This is followed by a pithy moral about being wary of wolves, not all of whom

run “on four legs. / The smooth tongue of a smooth-skinned creature / May mask

a rough wolfish nature...”

There’s yet another version

in which the girl and her grandmother defeat the wolf with their wits, but

Grimm would have had the same issue with that that he had with Hansel and

Gretel getting home on their own.

Perrault’s story of

Red Riding Hood has blatantly sexual overtones—the wolf has the girl join him

in bed—but Grimm omits this. Perrault and Grimm seem to want the story to either

be about sexual or spiritual

awakening, while Rowling, through her imagery and symbolism, enmeshes both elements in Chamber of Secrets.

Murphy discusses

Perrault’s and Ludwig Tieck’s versions alongside Grimm’s. In Tieck the girl is

looking forward to her confirmation and receives a red cap from her

grandmother. Murphy writes that this most likely stems from “a folk custom of

wearing red...in honor of the feast of Pentecost, when confirmation is

customarily administered...” If Perrault’s is a cautionary tale and Tieck’s is an

early horror story—his ending is both humorous and gory—then Grimm’s is an

allegory of receiving salvation by the grace of God despite being a flawed

sinner.

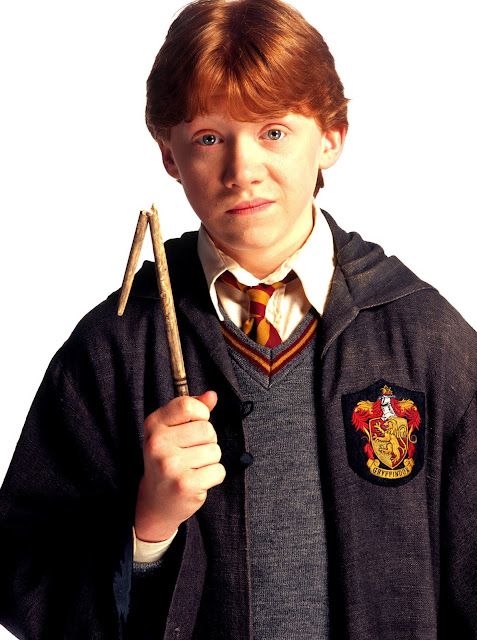

The girl in the

story is called “sweet” and everyone who lays eyes on her is fond of her. We

can easily transpose this description to Ginny Weasley. Grimm’s heroine

receives a red hood from her grandmother. Ginny’s red hair is her chief

distinguishing physical trait, a legacy from her parents and grandparents. Murphy

cites Bruno Bettelheim calling the red hood “a sign of female sexuality”, while in Murphy’s reading of Grimm, it is “a sign of the moment of spiritual maturity”, due to the tie to confirmation and Pentecost that’s more explicit in Tieck. Again, one can see sexual and spiritual maturity being equated, just as it is in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials books. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 12: Grow Up Now.)

Early in Grimm’s

tale the girl is told not to “go off the path” on the way to her grandmother’s.

In Chamber of Secrets we learn that

Ginny had a similar warning from her father. Near the end of the book, Arthur

Weasley says, “What have I always told you? Never trust anything that can think

for itself if you can’t see where it

keeps its brain.” Both girls are going to a place connected to their family

heritage, they’re on the cusp of knowing the difference between good and evil,

of being sexually and spiritually mature, but they both fall prey to a Tempter.

When Red Riding

Hood first encounters the wolf in Grimm’s story she’s not afraid, because she

“did not know what a bad animal he was”. Ginny thinks of Tom Riddle as “a

friend I can carry round in my pocket.” Murphy calls the girl’s reaction “a

statement of prelapsarian innocence”—which means innocence like Adam and Even

had before the Fall, before they knew about good and evil, which also seems to

be how we’re supposed to regard Ginny. This may be why Dumbledore holds Ginny

blameless. The fault lies with the “wolf”—Tom Riddle.

Murphy points out

that earlier versions had Red Riding Hood meeting the wolf in the village,

while Grimm moves this to the woods. According to Murphy, entering the woods “…is

to enter one’s grandparents’ and parents’ world, the continuum of the ancient

awareness of right and wrong by becoming capable of doing good and doing

wrong.” This

is the equivalent, for Ginny, of going to Hogwarts, where her parents,

grandparents and other ancestors learned to use magic responsibly, where they

learned to discern the right path.

Murphy sees the

wolf as “the Germanic equivalent for the serpent in the garden.” He mentions

the wolf Fenris from Germanic mythology, who, at the end of the world, is “to

kill the god Thor (and be killed by Thor’s hammer at the same time).” Like

Thor, Harry’s “emblem” is a lightning bolt: his scar. This encounter between

Thor and Fenris in Norse mythology is eerily similar to Harry’s battle with the

basilisk, since, at the moment that Harry kills the beast, he is also

penetrated by one of its fangs, which contains poisonous venom. It’s

undoubtedly no coincidence that, in the sixth book (which mirrors many elements

of the second) Rowling introduces a character called Fenrir, a werewolf who makes it a habit to prey upon children.

In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph

Campbell describes the battle at the end of the world involving Thor, Odin,

Fenris-wolf and the world serpent. He writes:

The dog Garm at the

cliff-cave, the entrance to the world of the dead, shall open his great jaws

and howl...Fenris-Wolf shall run free... The world-enveloping serpent of the

cosmic ocean shall rise in giant wrath and advance beside the world upon the

land, blowing venom.... [Odin] shall advance against the wolf, Thor against the

serpent....Thor shall slay the serpent, stride ten paces from that spot, and

because of the venom blown fall dead to the earth. [Odin] shall be swallowed by

the wolf...

Wolf and snake are

conflated in Chamber of Secrets. Both

the basilisk and Tom Riddle, who plays the role of the wolf from the fairy

tale, are “snakes”. There may have

been numerous sources known to Grimm in which a wolf is linked to the devil, so

equating the tempting wolf of the fairy tale with the tempting serpent in the

garden hardly seems like a stretch. Another parallel is that, as an adult,

Riddle changes his name to Voldemort, but most people in the wizarding world

say, “He Who Must Not Be Named” or “You Know Who”. This is similar to folk

customs that forbid people to say the name of the Devil, substituting things like

“Old Nick”, due to superstitions that to name the Devil is the same as invoking

or summoning him. Similarly, no one wants to invoke or summon Voldemort by

saying his name, and this “game” becomes very real in the seventh book.

When the wolf asks

Red Riding Hood where her grandmother lives, she replies, “...under the three

great oak trees, underneath them are the hazelnut hedges...” In this passage,

Murphy believes that Grimm is indirectly referencing a Germanic god, Odin, to

whom the oak is sacred, which again reminds the reader of Fenris, the adversary

of Odin and Thor. The fact that it’s three

oak trees, however, evokes the Trinity, which brings the symbolism into Christian

times.

The hazelnut

reference can be considered another pagan element, since, according to Murphy,

“The hazel-nut hedge marks off sacred space in Germanic mythology, hazel sticks

being placed in a circle to create the sacred space required for a judicial

assembly with divine sanction in ancient times. Thus the hazel image is that of

a place of contest and divine judgment.”

Rowling converts

the hazel to the myrtle: Moaning Myrtle. Myrtle the plant can be grown as a

hedge and is known for its thick, protective, impenetrable foliage. It’s also a

symbol of Aphrodite and love, and the myrtle flower was often included in

bridal bouquets. Rowling may also have liked the Jewish story (if she knows it)

of a woman accused of and killed for being a witch who was turned into a myrtle

tree after her death. Part of the lore surrounding the tree also says that if

you chew myrtle leaves you can detect witches.

Like Ginny, who is

symbolically “swallowed” by her wolf, Red Riding Hood is swallowed whole by the

wolf. This allows the hunter to cut her and her grandmother, who was eaten

first, out of the wolf’s stomach, where they are alive and well. Murphy writes:

“The hunter’s identity

as the Savior, as Christ, is shown in the resurrection of the two women,

ancient and new, from the death which comes through succumbing to temptation,

sin.... Even after he deceives good persons...their souls still shine with the

red glow of their gifted spiritual light even in the darkness of his belly,

until Christ comes and descends into the darkness of their death and

performs...one of the favorite mysteries of medieval Christianity, the

harrowing of hell.”

Harry is the

woodsman/hunter/savior in Rowling’s version, descending into a metaphorical

hell to save Ginny from the wolf/snake who has tempted her, deceived her, removed

her volition, and drained most of her life-force. Unlike the woodsman in Grimm’s

tale, Harry is not the deus ex machina—another

entity assists Harry. This, in addition to Ginny’s red hair being the

equivalent of a Red Hood, adds even more Pentecostal imagery to Chamber of Secrets.

Despite Rowling

presenting a child/young adult as the protagonist, which means he should be the

one to resolve the plot, she seems to use the deus ex machina in the first two books to distinguish between

Harry-the-child and Harry the newly-born-hero, which he cannot become until the

end of the second book, after he spiritually matures.

In the two books

in which Rowling uses the deus ex machina,

Harry is still inarguably a child, and his achieving salvation on his own is

implausible; he hasn’t acquired the skills or maturity. But he does have

wholeness and purity of heart bestowed by an outside force: his mother Lily.

Her love, the power of wholeness, protects him and prevents Quirrell from

touching Harry without doing himself irreparable harm. Harry did nothing to

accomplish that; he is saved by outside agents active before he was born, in

addition to Dumbledore, another deus ex

machina in the first book, who pulls Quirrell off him when he returns to

Hogwarts.

Rowling uses the deus ex machina in the second book when

Harry makes his statement of faith in Dumbledore, the god-figure who embodies

the Godfather variant of the Wise Old Man archetype. This simple statement of

faith brings Fawkes the phoenix to Harry in the Chamber of Secrets. Fawkes is

carrying the Sorting Hat, and Gryffindor’s Sword is inside it. Fire is the

thing most associated with the phoenix, through which it dies and is reborn. As

I wrote earlier, the story of Pentecost says that Christ’s disciples saw the

Holy Spirit appear as tongues of fire on their heads; this is a sign of their

faith, their belief, and when this happens on Pentecost, they receive the

ability to speak in other tongues so they can spread the gospel.

Fawkes symbolizes

the Holy Spirit, but when he appears in the Chamber, creating Harry’s

Pentecostal moment, Harry already has the gift of speaking to those who are the

“Other”, a side-effect of Voldemort making him the accidental Horcrux. This

ability is displayed early in the first book, when Harry talks to the snake he

frees from the zoo, but it isn’t named until the second book, in which he has his

symbolic confirmation or bar mitzvah.

Harry is about to

turn thirteen, which is the “commandment age” for Jewish boys. Preparing for a

bar mitzvah includes learning to speak an unfamiliar language, in order to read

a portion of the Torah during the ceremony. (This is unfamiliar even to

children in Israel, many of whom grow up speaking Modern Hebrew, a different

language from Ancient Hebrew, just as Modern Greek is not the same as any

dialect of Ancient Greek.) Afterward, the boy is considered to be a man, a

responsible member of the community who must perform mitzvot—good deeds—and go on a fast at Yom Kippur.

Like Grimm’s

hunter, Harry uses a weapon to slay the basilisk, though a snake is standing in

for a wolf, rather than the other way around, which is what we get in Grimm’s

story. Harry uses the serpent’s tooth itself to stab the diary, freeing Ginny

from the metaphorical belly of the beast. They both leave the Chamber, having

spiritually and physically matured.

Rowling again makes good use of Fawkes, her symbolic Holy Spirit, by having him

heal Harry, so he doesn’t die. Fawkes also bears everyone—Harry, Ginny, Ron and

Lockhart—out of the symbolic hell of the Chamber.

Having reached

this milestone, Harry doesn’t encounter a deus

ex machina at the climax of the next book, and in each subsequent book

Rowling also refrains from using this device. It had its place in the first two

but it would be inappropriate in the rest of the books. Harry now has the

ability to save himself and others and no longer needs an outside force for his

salvation. The savior of the wizarding world needs no other savior.

Grimm didn’t

include his woodsman to “cop out”, and Rowling doesn’t rely on Fawkes to help

Harry because she couldn’t think of something else. He plays a very specific

role as the embodiment of the Holy Spirit and allows us to see that Harry was

still a child earlier, though he was on the cusp of adulthood, and needed to

cross over into adulthood before fulfilling the role of savior to all of

Hogwarts, but specifically Ginny, who represents all children who stumble

before learning the difference between right and wrong.

In an earlier post (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 11: Wargames),

I wrote about the seven thresholds Hagrid crosses with Harry in the first book that

each align with one of the seven books in the series. The first threshold was

when Hagrid brought Harry to Dumbledore in Surrey, Dumbledore being the best

embodiment of the Wise Old Man, the archetype ruling the first book in the

series. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 2: This Old Man.)

Just as the first threshold involved Hagrid flying

with Harry over water to bring him to Dumbledore in Surry, the second threshold

Hagrid crosses with Harry again involves a water-crossing: He delivers Harry’s

Hogwarts letter to him in the hut on the rock. If JK Rowling hadn’t made Uncle

Vernon desperate to flee the letters, Hagrid wouldn’t have needed to cross

water to reach Harry, and Harry wouldn’t have needed to cross water with Hagrid

again to leave the rock. I believe Rowling did this quite deliberately to

manipulate the circumstances because she wanted another water-crossing for Harry,

signaling another symbolic rebirth. Once again, he does this with Hagrid, an

archetypal Mother. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 4: Mother, May I?)

The link between this episode in the first book and

the second book of the series is very straightforward: this threshold-crossing

involves Hagrid delivering a letter to Harry, a piece of writing. In Harry Potter and

the Chamber of Secrets, Ginny Weasley is the character who best embodies

the Maiden, the ruling archetype for that book, and she not only features

prominently in JK Rowling’s version of a classic fairy tale—a piece of writing—but

she also spends the better part of her first year at Hogwarts writing—in Tom Riddle’s cursed diary,

which Harry also does before entering the Chamber to return both Ginny and

Hogwarts to life again.

Adapted

from the script for Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 13: Deus ex Machina, Copyright 2017-2018 by Quantum Harry Productions and B.L. Purdom. See

other posts on this blog for direct links to all episodes of Quantum Harry.

Comments

Post a Comment