Essay: The Anti-Player

Paradoxically, as a hero who constantly plays games

and plays them well, sometimes the most interesting thing about Harry Potter is

when he either refuses to play, or he plays, but he doesn’t play to win. In Harry Potter

and the Goblet of Fire, when Harry returns to the Gryffindor common room

after his name comes out of the Goblet, the celebration in his honor rivals the

most raucous post-Quidditch party. Earlier in the book we only hear about

Hogwarts students who are Quidditch players putting their name in the Goblet

(see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 17: The Goblet of Games), and Quidditch

also unites the first people who congratulate Harry—Fred, George, Angelina and

Katie—plus Lee Jordan, the Quidditch commentator.

In the case of the Goblet of Fire, Harry not only doesn’t

play to win when it comes to being chosen as a Triwizard Champion—he isn’t

playing this game at all, taking for granted that it is impossible for him to

cross the age-line created by Dumbledore to keep anyone under seventeen from

putting their name in the Goblet.

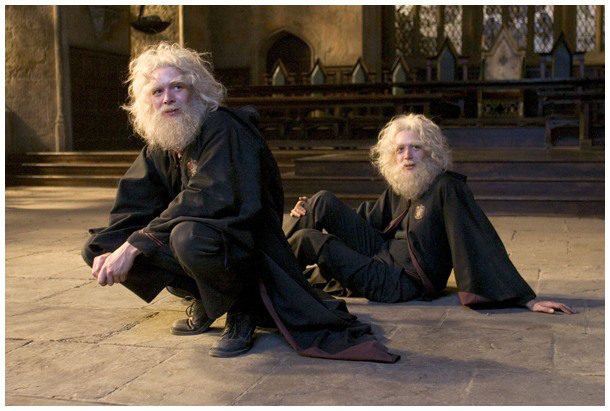

Harry sees Fred and George fail spectacularly at this game when their aging potion still gets them ejected from the

zone around the Goblet, and they temporarily sprout white hair and beards, taking

on the appearance of their archetype, the Wise Old Man (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 2: This Old Man). This also occurs in the previous book with Snape,

who is an archetypal Crone (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 6: A Murder of Crones). Snape takes on the appearance of his archetype in Prisoner of Azkaban when Neville battles

a boggart and it turns into Snape, first as he usually appears, then in clothing

habitually worn by Neville’s grandmother—a literal and archetypal Crone.

In the

fourth book of the Harry Potter

series, despite the lack of literal Quidditch after the World Cup,

brooms make frequent appearances in the narrative as metaphorical weapons. When

Rita Skeeter pulls Harry aside for a private interview, the confrontational

nature of this is highlighted by its taking place in a broom cupboard, a

metaphorical armory. Brooms

and flying come up again when Barty Crouch, Jr., disguised as Mad-Eye Moody,

asks Harry what he’s best at in an attempt to guide him toward the solution to

his problem of how to tackle the first task. Harry’s instinctive answer is Quidditch—a metaphorical war.

In the

first task, the Champions must get past dragons. The Quidditch similarities are

heightened because they’re each required to “catch” a golden egg, a virtual Golden Snitch. This egg specifically

resembles the Snitch Harry inherits from Dumbledore because it opens to reveal

a secret, but not just any secret: it is about retrieving the thing—or rather,

person—the Champion will miss the most. When Harry finally opens the Snitch he

caught in his first match, the Resurrection Stone brings him those he misses

most to be his honor guard as he walks to his death: his parents and the

parental figures of Sirius and Remus.

Each task

(the Yule Ball is also a task, so there are really four) is aligned with one of

the four alchemical elements of fire, air, water and earth, and each Champion

is aligned with a Hogwarts house, which in turn are also each aligned with one

of these four elements. As the Gryffindor Champion, from the house aligned with

the element of fire, Harry “wins” at the task also aligned with this element.

(See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 18: The Wide World.) He summons his

broom and swoops down on the egg as he would a Golden Snitch during a Quidditch

match, getting it from his dragon more quickly than the other champions. He

often considers his broom to be a weapon, and the first task of the Tournament

reinforces this.

When Harry

is working out the clue to the task aligned with the element of water—the

hostages in the lake—after holding the

egg underwater to hear the clue, he has a dream in which the mermaid in the

painting in the prefects’ bath holds his broom over his head, taunting him. In

this dream, his weapon is withheld from him because he doesn’t have what he needs

to accomplish this task.

Harry’s

innate power-sharing, his anti-player instinct, initially comes to the surface

when Hagrid shows him the dragons they’ll all be facing. Ever the fair-fighter,

Harry knows Viktor and Fleur will learn about the dragons from their head

teachers, so he must tell Cedric, to guarantee

a level playing field for all of them. Harry wouldn’t mind winning the

Tournament, but not unfairly, just as Cedric feels that he has an unfair

advantage during the Quidditch match in the third book when Harry falls off his

broom.

Harry,

Ron and Hermione each react negatively to a Champion based upon romantic

jealousy: Harry reacts negatively to Cho going to the Ball with Cedric; Ron

reacts negatively to Hermione going to the Ball with Viktor; and Hermione reacts

negatively when she hears that Ron has asked Fleur to the Ball and later when Fleur

kisses Ron on the cheek after he helps get her little sister out of the lake.

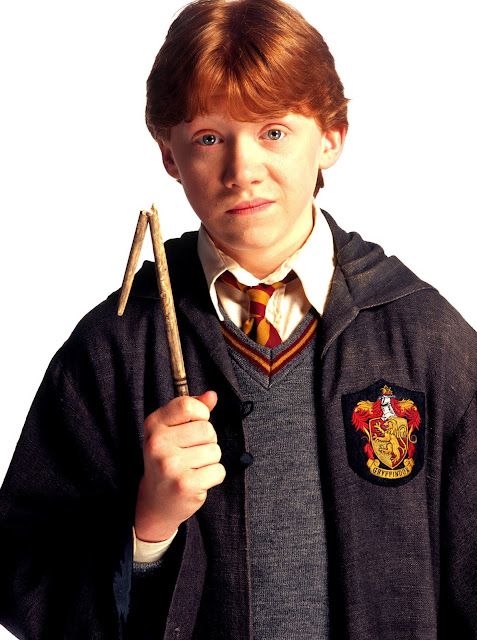

Hermione

is Viktor’s hostage and Cho Chang is Cedric’s. Ron is Harry’s hostage, serving

as a surrogate for his sister Ginny as the thing Harry would miss most now. Ginny later swaps places with Ron and

becomes Harry’s “best source of comfort”. The other male Champions are each rescuing

the girls they care most about while Harry rescues a stand-in for the girl he

eventually cares about.

Fleur’s

hostage is her sister, not a romantic partner or a surrogate for one. Gabrielle

Delacour is also the only hostage to whom Harry has no emotional attachments,

unlike Cho, the girl he fancies, and Ron and Hermione, his best friends. He still

feels compelled to rescue her with the others, again sharing power, behaving as

an anti-player, regardless of whether this will hurt his chances of success.

Making sure the hostages are all safe is more important to him than winning.

He’s convinced that the mock war has turned real, and when it’s revealed to the

tournament judges that he attempted to save all four, he gets high marks for

this. He’s the story’s chief “soldier” and player, yet he’s consistently

depicted as an anti-warrior and anti-player who doesn’t strive for victory at

any cost.

The

choice of hostages is another way, besides the Yule Ball, that Rowling enmeshes

romance into the competition; the game is one of both love and war. The

“pairing” of each member of the Trio with a Champion of whom they are jealous

points to this. We also get a Trio-and-Counter-Trio scenario that foreshadows

the Trio-and-Counter-Trio in the next book. Here the Counter-Trio is Cedric, Viktor

and Fleur; they are parallel to Neville, Ginny and Luna, the Counter-Trio that

accompanies the Trio to the Ministry in Order

of the Phoenix. They are also Harry’s, Ron’s and Hermione’s doppelgangers,

respectively, in the fifth book (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 7: Fountain of Youth).

Cedric,

the Champion Harry is jealous of, is equal to Neville, Harry’s doppelganger in the

fifth book’s Counter-Trio. Cedric is a Hufflepuff and Professor Sprout, his

head-of-house, is the Herbology teacher, the job Neville will eventually hold

as an adult. Neville and Cedric also both embody the archetype of the Father

(see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 5: Our Father).

Viktor

Krum, the Champion Ron is jealous of, fills the same role in his Counter-Trio

as Ginny, Ron’s doppelganger, serves in hers, because in Order of the Phoenix, during her first match as a Seeker for

Gryffindor, Ginny does exactly what

Viktor Krum does in the World Cup

final: she catches the Snitch knowing that doing so secures a victory for

the other team, and she does this as an

act of mercy, to end an excruciating game for her brother, Ron. When she

does this, this marks her as another anti-player, like Harry and like Viktor. JK

Rowling says that Ginny will become a professional Quidditch player later, like

Viktor Krum. Ron and Viktor are also both Wise Old Men.

Fleur,

the Champion Hermione is jealous of, fills the same role in her Counter-Trio as

Luna Lovegood, Hermione’s doppelganger, does in hers. Luna is the

“anti-Hermione”, a doppelganger with inverted versions of many of Hermione’s

attributes. Luna is also fascinated by Ron for a little while in the fifth

book, hanging on his every word and laughing uproariously at every little thing

he says, plus displaying detailed knowledge of his limited dating history.

There is also a superficial physical resemblance between Luna and Fleur, both

blondes with light-colored eyes, and one is an actual Ravenclaw while the other

is a virtual Ravenclaw, since the Beauxbatons students sit at the Ravenclaw

table while they are at Hogwarts. And finally, Fleur, Hermione and Luna create

yet another Maiden/Mother/Crone triad (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 3: Iron Maiden).

Ron

treats the Yule Ball as a real—not metaphorical—war, saying that Hermione is “fraternizing

with the enemy”, despite previously hero-worshipping Krum, including Ron buying

a small replica of the Bulgarian Seeker at the Quidditch World Cup. This sounds

like a kind of wizard “action-figure”—a

toy, in other words. The figure is later found maimed in Ron’s dormitory.

Fortunately, it doesn’t seem to work like a voodoo doll and Viktor suffers no

physical injury after Ron (presumably) vents his feelings on it.

The

location of the final task is another sign of the Tournament being the

metaphorical war replacing Quidditch in the fourth book, since it takes place

in a maze on the Quidditch pitch. If Harry or other students really thought

about it, they probably wouldn’t have decided that it was logical to have no

Quidditch for an entire year, since there are only three Tournament tasks, four

when you count the Yule Ball, and most students aren’t participating. There are

usually six Quidditch matches over

the course of about eight months.

However,

the Tournament serves functionally as a replacement for Quidditch in the book’s

plot, so whether this makes sense to the students isn’t a consideration for

Rowling. Quidditch is the chief metaphorical war in which Harry usually fights.

Two prominent mock-wars, both fought by Harry, would make the plot too crowded.

It makes sense on a meta-level for him to be attacked during the final

Tournament task, but this means that the Quidditch matches in which he might

have played would also have had to be related to genuine war, and Rowling doesn’t

seem to want the two activities competing. But even with two champions who are on

their house teams, there’s still no really good reason for the rest of the

school not to have a Quidditch season. Harry and Cedric could have been

excluded from Quidditch for one year, to let them concentrate on the Tournament, and other students could have played their positions. But no—if Harry isn’t

going to war during Quidditch, if it’s included just for sport, that doesn’t

fit her pattern.

As the

final task approaches, Rowling writes:

The start

of the summer term would normally have meant that Harry was training hard for

the last Quidditch match of the season. This year, however, it was the third

and final task in the Triwizard Tournament for which he needed to prepare...

She

links the year’s last match and the last task, a comparison heightened by the

site of the task. The maze being grown on the pitch points to this task

aligning with the element of earth, and the center of the maze is a

metaphorical “home”, the champions’ goal. This was usual for a medieval

labyrinth, which is shaped like a circle and cross gameboard, which in turn

looks like a common symbol for the earth. On top of this, when Cedric—a

Hufflepuff, the house aligned with the element of earth—and Harry take the Cup

together, they’re transported to a

graveyard.

Earth

to earth; ashes to ashes; dust to dust.

Ludo Bagman

shows the hedge maze to the Champions in its early stages and says that they’ll

have to get past obstacles in the maze. This is followed by Viktor asking Harry

about his relationship with Hermione, which Viktor is relieved to learn is

platonic. Right afterward, Harry and Viktor see Barty Crouch, Sr., a virtual

prisoner of war who has escaped his house, no longer under the Imperius Curse

his son placed on him. But Crouch isn’t quite in full possession of his

faculties when they meet him on the school grounds. By the time Harry fetches

Dumbledore, Crouch is gone and Krum is on the ground, stunned. “Moody”—really

Barty Crouch, Jr.—volunteers to find Crouch, Sr., his own father, so he can

kill him before his father can talk.

Harry,

Ron and Hermione are mystified about why Harry wasn’t attacked and Viktor was

attacked. They have no explanation, just as there’s no explanation for Harry not

being attacked earlier in the school year. But we do know why: this isn’t a

game or even a game-like battle, the type of venue in which Harry must always be

attacked. In addition to the feeble non-explanation for there being no

Quidditch season at Hogwarts in Harry’s fourth year, the failure of Barty Crouch,

Jr. to abduct Harry and take him to Voldemort on the first of September could

be seen as a huge plot hole, since no reason is given in this or subsequent

books for why Voldemort waited until June. However, the meta-reason is that

this is the author’s modus operandi. Mock

wars must morph into real wars. Another construct will not do.

Through

his scar, Harry sees Voldemort torture Wormtail. When he goes to Dumbledore to

talk about this, he finds Fudge and the fake-Moody with Dumbledore in the

headmaster’s office. Dumbledore sees his guests out, and while Harry waits for

Dumbledore to return, he enters the Pensieve belonging to the headmaster, a

bowl of liquid memories that lets him see past events that Dumbledore has been

mulling over. In more than one memory he sees an arena-like courtroom, a place

of confrontation resembling a venue for games, foreshadowing his being in the

same arena in the next book (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 22: The Phoenix Games).

However,

Harry still has an arena to deal with in the present. One of the obstacles in

the maze on the Quidditch pitch is a sphinx. In Greek mythology, Oedipus also

met a sphinx and had to answer its riddle: “What is the creature that walks on

four legs in the morning, two legs at noon, and three in the evening?” Oedipus

gives the correct answer: “Man,” because a baby crawls on all fours, then

learns to walk upright, and finally, must walk with the help of a stick as an

elderly person (the third leg).

The

riddle that the sphinx in the maze asks Harry to solve has “spider” for its

answer, but the first part of the riddle produces the word “spy”. This is not

long after Harry sees Dumbledore refer to Snape as a spy in the Pensieve. Soon

afterward, Harry sees a giant spider, an acromantula, about to attack Cedric.

Unlike the last time Harry went up against giant spiders, he’s not saved by the

Ford Anglia, living wild in the forest as a woods-car, the savior that rescued Harry and Ron from the spiders in Chamber of Secrets (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 13: Deus ex Machina). Instead, when Cedric trips and drops his wand while the

spider bears down on him, Harry distracts it by throwing spells at it, so it

attacks Harry, lifting him into the air until he finds a spell that works on

the spider—his signature move, Expelliarmus, the move of an anti-player—which makes the spider drop him.

The

fall from around twelve feet makes Harry’s previously-injured leg even worse,

so after he and Cedric succeed in stunning the spider by aiming at its soft

underbelly, he’s unable to run to the cup. He tells Cedric to take it, but Cedric

tells Harry to take it, since he saved Cedric twice in the maze. They disagree

and both refuse to take it: they are both being anti-players here, neither one jumping at the chance to win just because he can. Finally, Harry suggests that they take it together

and this appeals to Cedric’s innate fairness and power-sharing. Because of

Harry’s injured leg, as they walk to the cup, Cedric serves as a walking stick

for Harry—just like in the riddle that Oedipus solved. However, the moment they

take the cup together, they are plunged from metaphorical war, though a

dangerous one, into a real war, and soon after they arrive in the graveyard in

Little Hangleton, Cedric is dead.

Games

don’t disappear once Harry is plunged into a real war: dueling with Voldemort.

After Voldemort regains his body and gathers his Death Eaters, he prefers to

confront Harry alone. The Death Eaters create a circle around them, an

impromptu arena. A similar arena is created around them during their duel in

the seventh book.

Harry

is bound to a tombstone by Voldemort, a symbolic crucifixion. When he’s

released, the battle with Voldemort takes on the characteristics of a game, not

surprisingly. Rowling writes:

Voldemort

raised his wand, but this time Harry was ready; with the reflexes born of his

Quidditch training, he flung himself sideways onto the ground; he rolled behind

the marble headstone of Voldemort’s father, and he heard it crack as the curse

missed him.

“We are not

playing hide-and-seek, Harry,” said Voldemort’s soft, cold voice...

Harry

links his reflexes to Quidditch, the mock-war in which he is a stellar fighter,

while Voldemort compares it to hide-and-seek, a children’s game Harry is

reminded of in the seventh book when Voldemort is waiting for him in the

forest. Harry-the-anti-player decides that he’s no longer playing games. He’ll

stand and die like his father, the archetype that rules the fourth book. This

foreshadows his decision to throw off his Invisibility Cloak in the last book,

presenting himself to be killed, also the act of an anti-player.

What

gives Harry a victory here is shared power: Fawkes’s power. Harry and Voldemort

each have a feather from Fawkes the phoenix in their wands. As though the

feathers miss being together, united, the spells they cast cause the wands to

link. Their wands are yet another example in the series of metaphorical quantum entanglement, and the resulting cage of light

resonates with phoenix song, giving Harry hope and evoking the god-figure, Dumbledore,

Fawkes’s owner, just as Fawkes was Dumbledore’s agent, a symbolic Holy Spirit,

in the Chamber of Secrets (see Quantum Harry, Episode 13: Deus ex Machina).

The

wands link because no one disarms Harry.

When he arrived in the graveyard, his scar hurt him and “his wand slipped from

his fingers”. When Wormtail returns Harry’s wand he is still its master. Voldemort doesn’t think about the Wand Game

rules—or games in general—so this is a missed opportunity. Harry’s will probably

couldn’t have prevailed over Voldemort’s after their wands linked if he were not master of his wand. This incident also leads Harry’s wand to consider Voldemort an enemy, so it acts on its own against Voldemort in the final book,

when Harry leaves Privet Drive. Once

again, even though Harry didn’t sign up to play a game—as he didn’t sign up to

be in the Tournament—he is playing one anyway.

The

ghostly shades emerging from Voldemort’s wand are a reprise of the archetypal Wise

Old Man (this time it’s Frank Bryce), the Father (James and Cedric, both archetypal Fathers) and the Mother (Lily), the

archetypes that accompany Harry at significant times in his life (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 5: Our Father). These images distract Voldemort and

the Death Eaters, foreshadowing Harry’s loved ones being an honor guard for him

when he willingly walks to his death. The phenomenon with the phoenix-feather

wands also foreshadows the Elder Wand’s refusal, entangled with Harry as it is,

to act contrary to his will during their final duel, just as brother wands will

refuse to fight each other. Harry

will play the Wand Game with Voldemort twice more and win each time—the last

time for good. But that last time he will once again triumph with his signature

move: the Disarming Charm, the spell of an anti-player.

In previous essays on this blog, I've written about how the seven obstacles to the Philosopher's Stone align with the seven books in the series, so far covering the first three obstacles and books. The first obstacle Harry

encounters is a three-headed

Cerberus-like dog that is guardian of an underworld, evoking the symbolic death

that is necessary before achieving immortality through the Philosopher’s Stone.

The second obstacle is Devil’s Snare, a deadly plant that evokes the snakes, literal

and figurative, of the second book. It also requires sunlight, which is how

Harry conquers the Basilisk—through his statement of faith in Dumbledore, which

brings Fawkes the Phoenix to him (phoenixes being entangled with fire and with the sun), bearing the Sorting Hat with the sword of

Gryffindor. The third obstacle, the flying keys, is like practice for a Seeker,

and this obstacle aligns with the one book built around literal Quidditch (see

Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 10: All’s Fair in War and Quidditch and

Episode 11: Wargames). It also involves a quest for a key that recalls Harry

freeing Sirius and Buckbeak.

The fourth obstacle to the Philosopher’s

Stone is the life-sized chess game, a literal game and a literal battle, rather than a battle that resembles a game.

This involves all three of the friends in the Trio, though Ron decides on the

moves for Harry’s side. He sacrifices himself to achieve victory—another anti-player

move—but since Harry and Hermione are also players, they’re all potentially in

danger. No one is safe.

Professor McGonagall provides this

obstacle; she teaches Transfiguration, a theological term referring to a

manifestation of God. In the chess game, Harry is in the role of a bishop, a

link between heaven and earth, as Jesus is considered to be at the moment of

his Transfiguration. McGonagall is also the only female character embodying the

Father archetype, which rules the book that is built around the Triwizard

Tournament, a life-sized board game (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode17: The Goblet of Games). This is foreshadowed by the first book’s life-sized

chess game.

The chess game parallels the Tournament in

many ways. Harry is equal to himself, for obvious reasons. That he goes to a place

of death—a graveyard—but returns, is reflected in his role as a bishop, a

position of heavenly, not earthly power, a Liminal Being who crosses

thresholds, who can cross over into the world of death and return (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 8: Have You Tried Not Being Liminal?).

This is where the earlier comparison of

the two Counter-Trios, from the fourth and fifth books, comes in handy again. Neville,

a combination of Gryffindor and Hufflepuff, is not technically in the chess

game, but he and Cedric correspond to each other in the two Counter-Trios, since

Cedric is a Hufflepuff while Neville is a pseudo-Hufflepuff. They also embody

the same archetype: the Father. When Hermione puts a full-body bind on Neville—an

interesting choice of spell—this makes him similar to a corpse with rigor

mortis, while Cedric becomes a literal corpse. Cedric is also the one who does

not survive the Tournament, while in the first book, Neville, his representative,

doesn’t even get started. He stays in the Gryffindor common room, immobile,

while Harry, Ron and Hermione go to protect the Philosopher’s Stone. There’s also a parallel between Neville and Cedric at the ends of the first and fourth

books, when Dumbledore toasts to each of them during the Leaving Feast, though

he is rewarding Neville for standing up to his friends—as Dumbledore stood up

to Grindelwald—and he is memorializing Cedric.

Hermione is at a disadvantage at chess,

just as Fleur does not perform impressively in the Tournament despite being her

school’s champion. In the Counter-Trio of the fourth book, Hermione’s

doppelganger is Fleur, while Luna is her doppelganger in the fifth book’s

Counter-Trio. Luna’s link to chess is that in the seventh book, Ron calls the

Lovegood house a “rook”—another name for the castle in chess. This is the role that

Hermione plays during the chess game.

Ron is again linked

to Viktor Krum, both of them archetypal Wise Old Men. In the fourth book,

Viktor makes a sacrifice in the Quidditch World Cup that helps others. Ginny is

Viktor’s equal in the fifth book’s Counter-Trio and Ron’s doppelganger, and she

makes the same sort of sacrifice that Viktor does in the World Cup the first

time she plays Seeker in place of Harry. She makes this sacrifice largely for

Ron’s benefit. Thus, Ron’s sacrifice in the chess game foreshadows Viktor’s

World Cup choice and Ginny’s later choice.

In other words, in

the chess game that foreshadows the World Cup and the Tournament with the labyrinthine maze whose center must be

reached, as if the champions are on a giant Ludo

or Parcheesi board, both of which are

based on an ancient game board that looks like a symbol for the earth (or the

world), Ron’s sacrifice helps Harry to move

forward, making the chess game a clever summation of the fourth book, in which

the Triwizard Tournament is a life-sized circle-and-cross game instead of a

chess game. In this chess game, at the beginning of the series, Harry sees an

example of the type of sacrifice Viktor makes at the World Cup, and the type of

sacrifice Ginny, his partner and equal, will also make before Harry, the anti-player,

makes the ultimate sacrifice, laying down his life to defeat Voldemort.

Adapted from the script for Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 19: Not Playing to Win. Copyright 2017-2018 by Quantum Harry Productions and B.L. Purdom. See other posts on this blog for direct links to all episodes of Quantum Harry.

Comments

Post a Comment