Essay: Bonfire of the Phoenix

In previous essays I’ve written about Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets being JK Rowling’s version

of “Little Red Riding Hood” (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 12: Grow Up Now,

Episode 13: Deus ex Machina and Episode 14: The Devil’s Game).

However, Order of the Phoenix is her

version of an historical event: the Gunpowder Plot, the 1605 attempt by a group

of Catholic rebels to blow up Parliament and put a Catholic-friendly monarch in

power. The defeat of this rebellion has been celebrated each year since, on the

fifth of November, as Guy Fawkes Day, also called Bonfire Night.

This might seem like a break from Rowling using elements connected to

children and childhood for her underlying structure and thematic continuity.

However, the most important reference point for this book happens to be the only event in British history that’s commemorated

by fireworks and playful celebrations, a chance for everyone in the UK, and

many Commonwealth countries, to be like children, to take the day off to

celebrate, dance around a bonfire, and ask for “a penny for the Guy”, the

practice of children going door to door to ask for money to make Guy Fawkes

effigies to burn on the community bonfire, a tradition related to something

else children do at about the same time of year: trick-or-treating on Halloween.

In the previous books, JK Rowling wrote about games that are mock-wars

evolving into real battles. Here we have the flip side: more than one literal battle

in this book has the overtones of a game.

Bonfire Night has also evolved from its grim beginnings. It’s now a festive,

light-hearted holiday, but it began as a political crisis involving religious

oppression, torture, injustice, political corruption, conspiracy, attempted

assassinations, terrorism and attempted terrorism, and treason. Despite that,

the holiday is anything but serious today. Many Catholic UK residents celebrate

as whole-heartedly as non-Catholics, evidently not caring how the holiday began.

It’s a day of fun for everyone. A day to revel like children.

Despite the ubiquity of Guy Fawkes Day parties in the United Kingdom,

there’s only one mention of it

anywhere in the Harry Potter books: a

Muggle news reader suggests that premature celebrations of Bonfire Night might

explain the “shooting stars” and firework-like explosions Muggles witness when

wizards celebrate Voldemort’s fall after he kills James and Lily Potter and

attempts to kill Harry on Halloween night in 1981. It’s worth noting that the

newsreader calls it “Bonfire Night”—the name “Guy Fawkes” is conspicuously absent.

Not once in the Harry Potter novels

is there a hint that wizards observe this holiday, another indication, in

addition to the Irish national Quidditch team representing the whole of

Ireland, both Ulster and the Republic, that Muggle and wizarding political

distinctions are not the same.

There’s a huge Halloween feast at Hogwarts but there’s no mention of a

Bonfire Night celebration five days later in any of the six years that Harry is

a student. There are also no references to it in Quidditch Through the Ages or

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. Harry and Hermione, as well as

Dean Thomas, who are all Muggle-raised, also never note the conspicuous absence of this holiday in the wizarding

world, let alone noting that absence and the ‘coincidence’ of Dumbledore’s pet phoenix

being called Fawkes.

There’s little reason to believe that JK Rowling has a political or

religious axe to grind concerning Bonfire Night or that she’s flexing her

iconoclast muscles by reminding people that it started as an anti-Catholic

celebration, since she doesn’t do either of those things. She grew up in the

Church of England and now belongs to the Church of Scotland. She’s a Protestant, not a Roman

Catholic, and it’s highly unlikely that she wishes Guy Fawkes and his cohorts

had overthrown the government in 1605, just as British author Diana Wynne Jones

is also unlikely to have wanted that even though her novel Witch Week depicts an alternate reality in which Guy Fawkes succeeds in blowing up Parliament—but he’s

still caught. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 8: Have You Tried Not Being Liminal?)

Rowling and Jones seem to be loyal citizens of the United Kingdom. This

doesn’t prevent either author from using elements of the Gunpowder Plot in

their writing, though Jones wrote an alternate history, while Rowling created

characters whose actions are analogous to the Gunpowder Plotters and created a

government whose actions echo those of the English government.

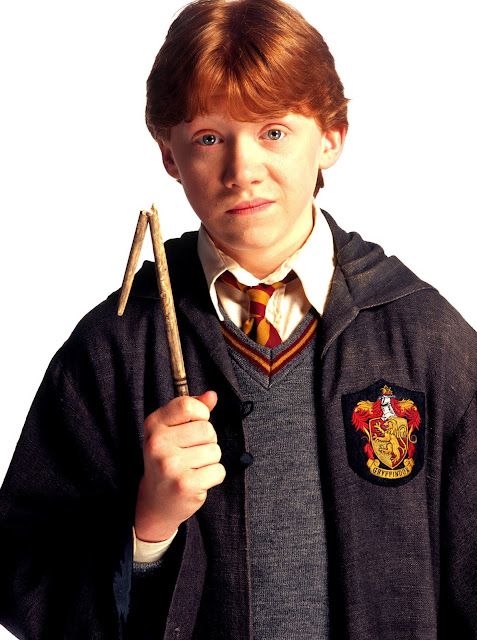

A Harry Potter reader in the UK might be concerned about Dumbledore’s very faithful pet phoenix being called Fawkes,

the name of the most notorious traitor in British history, or they might just

shrug it off as a joke, since phoenixes burn up and are reborn from their

ashes, while Guy Fawkes is burnt in effigy each November, yet the next year he’s

ready to be burnt again. Rowling is probably

joking around, but not because there’s no connection between her Fawkes and the

historical event that made Guy Fawkes famous. In addition to this somewhat

obvious joke, there’s abundant evidence that the name also alludes to the

historical events retold in Order of the

Phoenix in a somewhat warped fashion, as if seen in a funhouse mirror.

In contrast to the historical Gunpowder Plot, Rowling’s rebels triumph

over an oppressive regime in part by using fireworks and other creations of

Fred and George Weasley. Their fireworks are used against the establishment, not to celebrate a traitor’s defeat. So

even though there’s no literal celebration of Bonfire Night in the Harry Potter books, readers shouldn’t

assume that Rowling omitted this. It’s there, with a burning Fawkes, Catherine

Wheels, and a powderkeg under the seat of political power just waiting to go

off.

Harry receives a windfall after the Triwizard Tournament: a thousand

gold Galleons. He gives these winnings to the Weasley twins to finance their

business, since they produce “toys” and sweets that double as weapons. In

previous books, Harry receives house points, as he will in this one also, for

fighting real wars that then help to win a mock-war: the game-like battle for

the House Cup. In this case, Harry’s reward for winning the mock-war of the

Tournament is capital for the twins to make toy-like weapons for a real war.

Early in Order of the Phoenix,

the stage is set for Harry to be in the role of a rebel because the wizarding

government is already treating him as the enemy by trying to pre-emptively

discredit him. The Ministry attacks first; this is similar to the English Crown

attacking Catholics first, after Henry VIII established the English Church.

Catholics didn’t decide out of the blue to become traitors to their country;

the Crown made the first move.

At Grimmauld Place, Harry discovers that the The Daily Prophet has consistently been mentioning him in articles

as “a standing joke”. Hermione tells him:

“They keep slipping in snide comments about you. If some far-fetched

story appears, they say something like, ‘A tale worthy of Harry Potter’, and if

anyone has a funny accident or anything it’s, ‘Let’s hope he hasn’t got a scar

on his forehead or we’ll be asked to worship him next’–”

In the Harry Potter books, laughter

is a weapon against despair, but the Ministry tries to use it to dismiss Harry.

This chips away at his credibility before his hearing at the Ministry, but the

Ministry is using this tactic to discredit anyone

opposing this regime. In the Daily

Prophet, which has clearly become the propaganda wing of the Ministry, an

article about Madam Marchbanks resigning her court position and denouncing

Fudge tells readers, “For a full account of Madam Marchbanks’ alleged links to

subversive goblin groups, turn to page seventeen.” Soon the Ministry is not just waging ad hominem attacks.

The Ministry seems to think Harry can be easily dismissed because he’s

a kid. This dismissal of children happens repeatedly in Order of the Phoenix, and also happens every day in the real world.

(See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 1: The Kids’ Table.)

When Ginny is the only one not permitted to listen to information about

the Order of the Phoenix—Harry says he’ll tell Ron and Hermione everything—she

doesn’t take being treated as a child lightly, “raging and storming at her

mother all the way up the stairs”. War is all around yet discussions of it are

not considered appropriate for children, even children who will fight a real

battle by the book’s end. A hazard of fighting a war against children, as Voldemort learns to his detriment, is that

their youth and inexperience is deceptive and no indication of their true

power. We see this in a conversation between George and Harry:

“...size is no guarantee of

power,” said George. “Look at Ginny.”

“What do’you mean?” said Harry.

“You’ve never been on the receiving end of one of her Bat-Bogey Hexes,

have you?”

This book is full of similarly disregarded and dismissed entities:

children, house-elves, and “Mudbloods and blood-traitors”, as Mrs. Black’s

portrait screams whenever she’s disturbed. Later, Rowling reveals how Ginny

became good enough to be a Seeker:

“...Ginny’s not bad,” said

George fairly, sitting down next to Fred. “Actually, dunno how she got so good,

seeing as how we never let her play with us.”

“She’s been breaking into your broom shed in the garden since the age

of six and taking each of your brooms out in turn when you weren’t looking,”

said Hermione...

Even before they know this the twins aren’t lulled into thinking that Ginny

is someone to trifle with, despite not thinking she was up to their level of

Quidditch play—yet she’s the only character Rowling says will become a

professional player other than Viktor Krum. The Ministry, Voldemort, and

Umbridge all make the mistake of thinking that “size”, or rather, chronological

age, indicates someone who can be easily dismissed. Both Harry and Ginny

repeatedly disprove this.

Another

character dismissed by most people in her world, Luna Lovegood is the best

embodiment of the archetype of the Crone in Order

of the Phoenix, the book ruled by this archetype (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 6: A Murder of Crones).

Luna provides levity in the fifth book, in addition to the Weasley twins’ jokes

and games. While she might not find the same things funny that readers do who

identify as her fans, as a Crone she isn’t concerned with her beliefs meshing

with the rest of the world’s. Hermione is especially rubbed the wrong way by

Luna, JK Rowling’s “anti-Hermione.”

Mr.

Lovegood, Luna’s father, is editor and publisher of The Quibbler, a wizard tabloid with wild tales of extraordinary

creatures, conspiracy theories about Fudge baking goblins into pies, and Sirius

Black being a musician called Stubby Boardman. This so-called “rag” carries

Harry’s interview with Rita Skeeter, who embroiders on the truth more than a

little. A tabloid newspaper that is usually considered “fake news” turns out to

be more genuine than the so-called “real” news, The Daily Prophet, with its tales of Mad-Harry Potter, Power-Hungry

Dumbledore and Sirius-Black-the-Death Eater, which is as wrong as calling him a

secret rock star.

Luna,

like Trelawney, another archetypal Crone, sees what others can’t or don’t wish

to. When Luna tells Harry that she can see the Thestrals pulling the supposedly

horseless carriages and says to him, “You’re just as sane as I am,” he doesn’t

seem to find this comforting. Yet Harry has seen something that most people

disbelieve: the resurrection of Voldemort. He lives in a world most Muggles

cannot see or, in his family’s case, don’t want to think about, but there’s

still a division even in the wizarding world between those with faith in the

unseen and those who require concreteness and cold, hard facts, like Hermione,

who laughs at Luna’s ideas, though Harry asks her not to offend one of the only

people who believes him. Who believes what and in whom is a contentious issue

throughout the fifth book, which is appropriate for a book that’s about a

religious war.

Hermione

later has a change of heart; the two people she turns to in order to publicize

Harry’s story are Luna, the disregarded “loony” girl whose father produces a

wizard tabloid, and Rita Skeeter, who’s not always on speaking terms with the

truth (though many of her readers clearly don’t know this). A frivolous

throwaway paper will now be the only vehicle to communicate the truth. Rita,

however, points out a problem:

“The

Quibbler!” she said, cackling. “You think people will take him seriously if

he’s published in The Quibbler?”

“Some

people won’t,” said Hermione in a level voice. “But the Daily Prophet’s version of the Azkaban breakout had some gaping

holes in it. I think a lot of people will be wondering whether there isn’t a

better explanation of what happened, and if there’s an alternative story

available, even it if is published in a—” she glanced sideways at Luna, “in

a—well, an unusual magazine—I think

they might be rather keen to read it.”

Hermione

knows that Rita isn’t on their side but she threatens to turn her in to the

Ministry as an illegal Animagus if she doesn’t do what they want. Hermione may

not play the usual games for kids her age, but just as she “got” Snape’s

potions logic game, she knows that even a rag is taken seriously if it seems to

carry a true story, like a broken clock being right twice a day.

Hermione

may also have given some thought to Sirius chastising her for having the DA

meet in the Hog’s Head instead of at The Three Broomsticks, where they couldn’t

have been overheard as easily. Hiding in plain sight is sometimes best, and

Hermione plans for Harry’s story to hide in plain sight in a publication

usually dismissed by anyone who’s not a Lovegood.

Robert

Catesby was a higher-profile rebel than Guy Fawkes and was very likely the

mastermind of the Gunpowder Plot. Fawkes was a member of the group, though, and

it’s possible that he was “taking the fall” for Catesby when he was discovered under

Parliament with the gunpowder. This possibility may have given rise to the

erroneous and now-debunked idea that Fawkes was the origin of the phrase “fall

guy”, a person who accepts blame for something another person did. But even if

Guy Fawkes was a “fall guy” for a

co-conspirator, he was involved in

what amounts to a revolutionary organization that was opposed to the Crown’s anti-Catholic

laws. Members of Dumbledore’s Army were also really doing what Umbridge accused them of and had forbidden them

to do and Harry really did conjure a

Patronus in front of his cousin. Even though Rowling depicts her heroes as

analogous to the Gunpowder Plotters, she never does this by implying that they

weren’t doing exactly what they were accused of.

JK

Rowling may be perfectly aware that Catesby is considered “the prince of

darkness at the centre of the Gunpowder Plot”, rather than Fawkes. [Antonia Fraser, Faith and Treason: the story of the Gunpowder Plot (New York: Nan

A. Talese, 1996), p. 90.] She may even have been referring to another part of English

history earlier than Order of the

Phoenix, in the title of Chapter Seventeen of Prisoner of Azkaban, “Cat, Rat and Dog”. This may be a riff on a

satirical rhyme about William

Catesby, Robert Catesby’s father, who is the “Cat” in the rhyme, which is about

three supporters of Richard III, whose crest was a hog or boar, like the winged

boars at the gates to Hogwarts. This is the rhyme:

The

Cat, the Rat and Lovell our Dog

Rule

all England under the Hog.

[Fraser,

p. 91.]

If

the DA is equal to the rebels, Harry can be seen as Robert Catesby, if we

accept that the leader of the Gunpowder Plot wasn’t Guy Fawkes. Dumbledore, owner of the phoenix called

Fawkes, who is his avatar, then becomes equal to Guy Fawkes by taking the blame

for Dumbledore’s Army. Just as Guy Fawkes is burnt in effigy each fifth of

November—though sometimes effigies of the Pope were burned, and Dumbledore is a pope-figure—it’s fitting that Fawkes-the-phoenix

appears in Dumbledore’s office when Fudge is trying to have him arrested, and

then disappears in a burst of flame, taking Dumbledore to safety. The Gunpowder

Plot ended with the plotters imprisoned and then executed, and gunpowder, their

intended weapon, used for a celebration of their defeat for centuries to come,

while Rowling’s Guy Fawkes figure, Dumbledore, with help from a phoenix called Fawkes, escapes triumphantly, in a burst of flame.

As these essays have been progressing through each of the seven books

in the Harry Potter series, I’ve been

examining how each of the seven thresholds Harry crosses with Hagrid’s help in

the first book aligns with one of the books. This is yet another set of

recursive links to the seven books in the series, in addition to the seven

obstacles to the Philosopher’s stone each aligning with one of the books and

each book having a ruling archetype. Just as with the previous books, the link

between the fifth threshold-crossing and the fifth book is also entwined with

the ruling archetype for this book.

To recap, the first threshold is Harry crossing water with Hagrid to go

to Surrey, where Hagrid delivers him to Dumbledore, the best embodiment, in the

first book, of the Wise Old Man (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 2: This Old Man).

Hagrid does this in the book ruled by the Wise Old Man archetype.

The second threshold is Harry crossing water with Hagrid again after

Hagrid brings him his school letter, a piece of writing, linking this threshold

to the second book and to Ginny Weasley, the best embodiment, in this book, of

the archetype of the Maiden (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 3: IronMaiden).

Ginny does this in the book ruled by the Maiden archetype, as well as playing

the role, in this book, of Little Red Riding Hood, the fairy tale—another type

of writing, like Harry’s Hogwarts letter—that Rowling retells in Chamber of Secrets.

The third threshold is Harry going through the wall of the Leaky Cauldron

with Hagrid to reach Diagon Alley. In the third book, Harry uses the

Time-Turner to dissolve walls in another way, freeing Sirius and Buckbeak from

captivity, with help from Hermione, the character in the third book who best

embodies the archetype of the Mother. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 4: Mother, May I?) They do this in Prisoner of Azkaban,

the book ruled by the Mother archetype.

The fourth threshold is Harry going underground with Hagrid to reach

his Gringotts vault, a symbolic underworld, a place for the dead, where he

withdraws gold left to him by James, his Father. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 5: Our Father.) This is echoed by Harry going to a graveyard, another place for the dead, in

the fourth book, which is ruled by the Father archetype. Harry goes to the

graveyard with Cedric Diggory, the character who best embodies the Father

archetype in Goblet of Fire, and

Harry is rewarded with gold upon his return from the graveyard.

The fifth threshold is another water-crossing, but this time all of the

students in Harry’s year undergo this ritual, this rite-of-passage. It is a

symbolic baptism. All new Hogwarts students must undergo this ritualistic

crossing because they are beginning new lives. That this is a symbolic baptism

links this threshold to the metaphorical religious war rocking the wizarding

world in Order of the Phoenix. It’s

fitting that, before entering into the symbolic state church of this world, all

first-years go through this ritual, a metaphorical rebirth.

Harry undergoes an analogous rebirth at the beginning of Order of the Phoenix, whose name is

about rebirth because that’s what a phoenix symbolizes. Harry is no longer

blind to the Thestrals who transport all students to the castle after the first

year, drawing carriages that Harry previously thought were moving due to a

spell. He has witnessed death—Cedric’s death, a re-enactment of his father

James’s death, in the book ruled by the Father archetype. After he returns from

the graveyard—which is to say, he symbolically returns from the grave, since he

has escaped death yet again—he is reborn with an ability he did not previously

have: he can see Thestrals—just as all first-year students are reborn as

Hogwarts students after they cross the lake with Hagrid, Keeper of the Keys.

Near the beginning of Order of

the Phoenix, Luna Lovegood, the character best embodying the archetype of

the Crone in this book, which is ruled by her archetype, tells Harry that she

can also see the Thestrals. The Crone can see across the barrier between life

and death (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 6: A Murder of Crones).

Crones see what most people cannot, and after Harry gains the ability to see

Thestrals, because he’s seen death, he shares this attribute with Luna. Harry

loses Sirius in this book, his godfather, someone who is a key player in a

baptism, and the threshold aligning with this book is a symbolic baptism. Luna,

the archetypal Crone, is the person who helps Harry to view Sirius’s death not

as an end but as a temporary separation from someone he loves, preparing him to

remove his Invisibility Cloak in the final book and embrace Death like an old

friend.

Adapted from the script for Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 20: The Order of the Rebel, Copyright 2017-2018 by Quantum Harry Productions and B.L. Purdom. See other posts on this blog for direct links to all episodes of Quantum Harry.

Comments

Post a Comment