Essay: The Game's Afoot

In the

world outside of Harry Potter, the

disregard many people have for books read by children, because they consider

them to be only for children, is

similar to other knee-jerk judgments people have had about Harry Potter, such as labeling the Harry Potter books evil because there’s magic in them, or calling

the series simplistic, two-dimensional and otherwise not worthy of adults’

attention, either to analyze or to read for pleasure. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 1:The Kids’ Table.)

With

the exception of professional sports (and even then, some people look down on

adults who they think are grasping at childhood when they play or watch sports),

games are also often dismissed in our world. Gamers get even less respect, if

possible, and are often stereotyped as adult male college graduates or

drop-outs living in their parents’ basements playing World of Warcraft, and never seeing daylight. Incidents like

Gamergate didn’t help the public image of gamers—and rightly so, in that case.

Yet

Jane McGonigal maintains in her book, Reality

is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World, that

we need to make reality more like

games. JK Rowling may or may not agree, but she structured her seven-book

series around toys, fairytales, games and the equipment for games, and the

archetypes that I call Rowling’s game-pieces. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 2:This Old Man.)

According

to Jane McGonigal, the four defining traits of a game are that it should have a

goal, rules, a feedback system (so you know how close you are to the goal) and

voluntary participation. However, she cites Bernard Snits’s definition of a

game as more succinct: “Playing a game is the voluntary attempt to overcome

unnecessary obstacles.” This is very much how JK Rowling uses games in the Harry Potter books; the reader

experiences this as a realization that Harry or another character is attempting

to overcome an evidently unnecessary

obstacle, and seems to be doing so voluntarily. This is probably because

the character in question is playing a

game. In Reality is Broken, McGonigal writes:

If the goal

is truly compelling, and if the feedback is motivating enough, we will keep

wrestling with the game’s limitations–creatively, sincerely, and enthusiastically–for

a very long time. We will play until we utterly exhaust our own abilities, or

until we exhaust the challenge. And we will take the game seriously because

there is nothing trivial about playing a good game. The game matters.

Part

of the appeal of the Harry Potter

books could be that Harry is a surrogate player for the reader, and in turn,

when people purchase the video games based on the books and films, players get

to be surrogates for Harry, or for Hermione or Ron, voluntarily overcoming unnecessarily

obstacles, working toward a goal, following the rules, and hoping that the

feedback will report that the player is coming closer to the goal. Whether

reading books or playing a game, the reader or player gets to play along with

Harry.

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

introduces the reader to Harry and the wizarding world. In the initial chapter

a holiday that’s fun-and-games for children, Halloween, turns deadly for

Harry’s parents. Soon after, Voldemort’s attempt to also kill Harry backfires,

and when news of this spreads, war segues into play for wizards, who celebrate

by setting off magical sparks mistaken for shooting stars and early fireworks

in celebration of Bonfire Night, the national holiday of the United Kingdom

that is another instance of war, or rather, rebellion against the state—The

Gunpowder Plot—becoming a playful celebration enjoyed by all. This is the only literal

mention of Bonfire Night in the seven-book series. From what we see, or rather,

don’t see, this is a purely Muggle holiday. (I have my own theories about why

that is, but that is for a future essay.)

In Philosopher Stone’s first chapter,

Rowling introduces readers to Harry’s uncle and guardian, Vernon Dursley,

married to Harry’s mother’s sister, his Aunt Petunia. Vernon is no fan of

imagination or laughter that’s not at someone else’s expense, nor people

dressing in “funny clothes”, such the wizards who are celebrating Voldemort’s

fall. Dumbledore’s introduction contrasts him directly with Vernon Dursley. Not

only is his taste in dress likely to produce a far more derogatory comment from

Vernon than merely “funny”, he’s fond of sweets. Sweets become weapons in Fred

and George Weasley’s war against Umbridge—Fred and George also being Wise Old

Men, the same archetype as Dumbledore. Their sweets are eventually a weapon

against Dudley Dursley, when he eats a Ton-Tongue Toffee in Goblet of Fire.

While

waiting on Privet Drive for Hagrid, Dumbledore offers a sweet to Professor

Minerva McGonagall. The passwords giving access to his office also happen to be

sweets. Dumbledore is very fond of his Famous Wizard Card, which children

collect and is only available with Chocolate Frogs. On the train, Ron indirectly

introduces Harry to his future general in the war, Dumbledore, through the

Chocolate Frog Card, a child’s plaything that comes with a sweet. Most people

don’t take toys, games, sweets or fairytales seriously, and also don’t take

seriously some of the people Dumbledore esteems most highly, such as Hagrid.

But Dumbledore values all of these things.

In the

next chapter, ten years have passed, and Harry learns that he’s a wizard. His

young life has seldom contained games. For ten years he’s been bullied by his

cousin Dudley, plus his Aunt Petunia, Uncle Vernon, and sometimes Aunt Marge

and her dogs. He lives in a cupboard. He’s fed very little. He has no friends;

Dudley has bullied other kids out of wanting to be his friend.

A year earlier,

for his tenth birthday Harry received a wire coat hanger and an old sock of

Vernon’s. Dudley’s birthday gifts include videogames, a television, video

cameras, and sports equipment that he’s unlikely to use. He has a second

bedroom to hold broken toys and games, plus unread books, and it’s significant

that this is where Harry comes to live

when he leaves the cupboard, in the repository for old games and toys, the

space for unread fairytales and other children’s books. (Dudley is unlikely to

have books for adults, being the same age as Harry.) Despite his birthday

bounty, Dudley’s favorite “game” is chasing and beating up Harry, which is more

like war than a game to Harry, who’s grown up with games, for Dudley, morphing

into wars for him. He was weaned on this; Harry does not get to have games for

games’ sake.

When

the Hogwarts letter arrives, Harry is starved for games that are only games, starved for a normal

childhood. Though inherently whole and complete, Harry is actually incomplete

while he’s with the Dursleys, who have deprived him of things Dudley takes for

granted: loving caretakers, games, toys and a carefree childhood devoid of

threats to life and limb. He’s also incomplete while ignorant of the truth

about himself and his parents.

Trying

to steal a letter from his uncle that’s addressed to Harry becomes a game that,

like his relationship with Dudley, is also a war, but his strategizing doesn’t

produce the result he wants. He rises early to get the post but his uncle has

risen even earlier and reaches the letterbox first. Vernon continues the

“game”, having them all flee across the country to avoid the letters. He drives

erratically, doubling back on his route, having them stay in places that make

Dudley howl for his television and computer, on which he likes to blow up

things. (Dudley’s games are all warlike.) But this is no game to Vernon; he’s

fighting a war. Vernon is, of course, going to lose.

When

Hagrid hand-delivers Harry’s school letter a new world opens to him. It is a

moment of sublime completion for Harry to finally know who and what he is. In

the language of Joseph Campbell’s hero cycle, Hagrid is the “herald”. Campbell

writes:

The herald or announcer of the adventure...is

often dark, loathly, or terrifying, judged evil by the world...

[Joseph Campbell, Hero with a Thousand Faces (Novato, CA: New World Library, 1979)]

This

is the case with Hagrid, especially when he’s vilified for being a half-giant.

But Harry quickly takes to Hagrid, the first person he’s seen do magic since he

was a baby. To him it’s the best game ever.

It takes him through a wall to Diagon Alley; it gives Dudley a curly pink pig’s

tail; and it gives Harry a new self.

He’ll eventually learn not to view magic as a game, but this is an

understandable initial reaction.

Hagrid

tells Harry that the purpose of the Ministry of Magic is to keep Muggles in the

dark about magic, telling him that everyone would want magical solutions to

their problems. It’s as if wizards are concerned that Muggles, who they regard

much like small children, would think of magic like a game, something to treat

lightly, as many wizards do. It’s unclear whether they feel that Muggles are more prone to do this or just as prone as wizards. One of the

most pressing messages of the books is that magic is not frivolous, let alone Harry’s most important attribute. His

wholeness and his ability to love are far more important. This is another

reason that criticism of the books due to the inclusion of magic is entirely

missing the point.

Harry’s

letter says that first years cannot have brooms at school, though they will

have flying lessons and many students from wizard families have probably

already flown on brooms. However, if we consider a broom as a weapon it makes

sense for this “toy”, used for transport and for a dangerous war-like game, to

be withheld from the youngest students except when they’re supervised.

In

Diagon Alley, Hagrid takes Harry to Gringotts, the wizarding bank, which is tantamount

to taking him to an amusement park where he’s given gold just for being him, a

dream-come-true game that’s been turned into a videogame, allowing Harry Potter fans to put themselves in

his place. As is the pattern throughout

the books, the “game” of riding through Gringotts in a small tram-car past

various obstacles to reach the gold is potentially dangerous. What neither we

nor Harry learn until later is that Professor Quirrell breaks into the bank on

the same day to try to steal the Philosopher’s Stone before Hagrid can complete

his errand and deliver it to Dumbledore.

This

means that at the beginning and end

of the book Harry is racing with Quirrell to reach the Stone, though Harry

doesn’t know this at the start, and at the end he thinks he’s in a race with

Snape. His entrance into the bank is accompanied by a rhyme that seems flippant

on the surface but is quite serious:

Enter stranger, but take heed

Of what awaits the sin of greed

For those who take, but do not earn,

Must pay most dearly in their turn,

So if you seek beneath our floors

A treasure that was never yours,

Thief, you have been warned, beware

Of finding more than treasure there.

This

isn’t the only “game” during Harry’s trip to Diagon Alley. Draco Malfoy first

mentions Quidditch to Harry in Madam Malkin’s robe shop. This foreshadows many

things: Draco taking Neville’s Remembrall, which Harry retrieves, landing him

on the Gryffindor Quidditch team; the midnight duel challenge; Draco and Harry

facing each other in the Dueling Club in the next book; and Harry and Draco

being rival Seekers in the second book.

Draco being the first to mention the

most prominent wizarding game and the one that informs much of the action in

the seventh book (though literal Quidditch is technically absent from it)

doesn’t just set up these conflicts, it positions him as Harry’s enemy in

general. The word “Quidditch” being introduced by an enemy is important. He

throws down a challenge to Harry, who must rise to this challenge throughout

the series.

Though

Harry is not permitted a broom he acquires another weapon in Diagon Alley: a

wand. Harry still considers magic as something of a game, and little occurs in

Diagon Alley to dissuade him from this view. The wand is equipment for this

“game”, though potentially quite dangerous. Like most powerful objects, a wand

is about potential; it matters how it is used and cannot be considered good or

evil on its own, though more than one person makes this sort of judgment

concerning the Elder Wand.

Mr.

Ollivander tells Harry that the wand that “chooses” Harry has the same core as

Voldemort’s because Dumbledore’s phoenix, Fawkes, has provided the feathers in

each. In the fourth and seventh books we learn other Wand Game rules, such as

the importance of the relationship between wand and wizard—especially whether a

wand recognizes a wizard as its master—as well as the relationship between

wands, like when Harry’s and Voldemort’s wands link in the fourth book. These

two wands, being “brothers”, will not work against each other. This is

metaphorical quantum entanglement; the wands are entangled, like Harry and

Voldemort themselves, because their cores were once part of the same entity,

Fawkes. And finally, a wizard cannot be harmed (unless it is his will to be

harmed) by a wand that recognizes him as its master, since master and wand are

also entangled, but we don’t learn about that

until later.

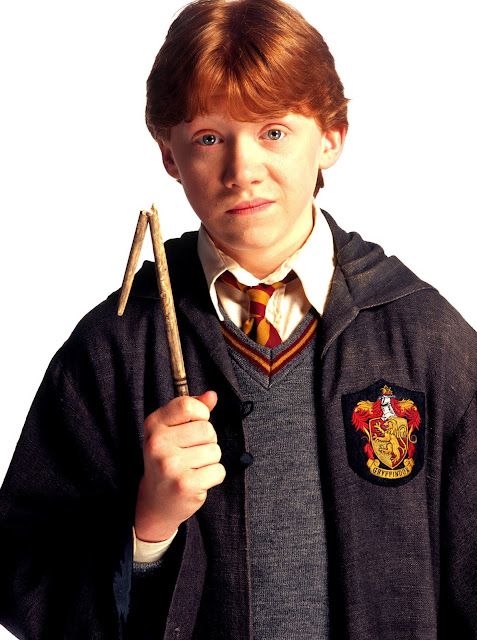

Ron is

the second person to discuss Quidditch with Harry. In contrast to Draco, this

binds Harry and Ron as friends and comrades, since Quidditch is metaphorical

war and they eventually become teammates. Ron is enthusiastic about the game

and wants Harry to love it as much as he does. Draco challenges Harry and is

neither friendly nor inclusive. Draco and Ron are doppelgangers, as are Draco

and Harry, for different reasons, and this is seen in the contrast in how they

discuss Quidditch with Harry. They’re both of the wizarding world and

interested in “their” sport, but one cautiously sizes up the newcomer as a

potential adversary while the other shares his love of a game without

considering whether the pointers he gives could be used against his side. When

they’re on the train Ron doesn’t know which houses he and Harry will be in—for

all they know, they could end up cheering for different house teams for seven

years.

Another

game in the first book that’s played by both Ron and Hagrid is the Name Game—in

other words, saying “He Who Shall Not Be Named” or “You Know Who” instead of

“Voldemort”. Neither Dumbledore nor Harry play this game and Ron is impressed

by what he perceives as Harry’s bravery, though Harry simply hasn’t been conditioned to play this game, as Ron was.

Harry not accepting the basic rules of the Name Game becomes an issue in the seventh

book.

Hagrid is another

doppelganger for Harry in the first book. He instantly recognizes Harry as an outsider, though in a slightly

different way than the friendly half-giant. Hagrid was expelled from Hogwarts

and Harry is worried about this happening to him when he disregards Madam

Hooch’s instructions to stay on the ground during the flying lesson. The contrast between sharing power and abusing

power is highlighted here when Draco Malfoy steals Neville Longbottom’s

Remembrall and Harry gets it back.

It’s significant, first, that Draco steals something

from Neville linked to memory, since

Death Eaters “stole” Neville’s parents’ memories. Draco, the son of a Death

Eater, steals the Remembrall, and this is an echo of the attack that took

Neville’s parents’ minds, which is an inarguable abuse of power. This incident

also foreshadows the first task of the Triwizard Tournament, in which Harry

uses his broom to “catch” an egg from a dragon, an egg that is a stand-in for a

Snitch, while in the incident from the first book, Harry is trying to catch a

Snitch-equivalent from someone whose name means

dragon: Draco. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 5: Our Father.)

Harry and Neville are also doppelgangers because

either of them could have fulfilled the prophecy and Voldemort is, directly or

indirectly, responsible for each boy growing up without his parents. Harry’s

response to Draco could be seen as an

abuse of power—the students were told

to stay on the ground—but he doesn’t seek power for himself and he fully expects to be punished—expelled, even—when

Professor McGonagall marches him off to the castle.

Neville is powerless, unable to control his broom or

keep his property, while Harry shares

his power by retrieving the Remembrall. In addition to this foreshadowing the

first task of the Triwizard Tournament, this also foreshadows an inversion of

this scene in Order of the Phoenix,

when Neville attempts to help Harry with the prophecy orb in the Department of

Mysteries. Part of the inversion is that while Harry succeeds in saving the

Remembrall, Neville fails to preserve the orb. Both the Remembrall and the orb

are linked to memory; the Remembrall

is supposed to help Neville remember things, and the prophecy orb contains the

memory of the prophecy that could have involved either boy, until Voldemort

chose Harry.

The Snitch Harry catches in his first match is also

linked to memory, since Dumbledore encases the Resurrection Stone inside this

Snitch and leaves it to Harry in his will. The Snitch “remembers” Harry and this

allows him to open it when he is about to die, so he can use the Resurrection

Stone to call up the shades/memories of people he loved and lost, who accompany

him as he walks to his death.

In Half-Blood

Prince, Cornelius Fudge says to his Muggle

counterpart, “The trouble is, the other side can do magic too, Prime Minister.”

This is why Quirrell is correct to say “there is no good or evil, only power”.

The Prime Minister can’t understand why wizards are having trouble with

Voldemort, but the answer is simple: different attitudes towards power. Fudge verbalizes the conflict at the

center of the sixth book, the problem Harry has to solve before the end of Deathly Hallows.

It’s important that the prophecy says that Harry is

the one with the power—not the destiny—to defeat Voldemort, he has a

power that Voldemort “knows not”. We

could call it Love, or Game-Fu—in other words, valuing and understanding games,

toys and fairy tales. It could also be a combination of these, or yet again, it

could be a causality, so that, in the

end, Harry’s ability to love is also what enables him to value games, toys, sweets,

fairy tales, and childhood itself, all of which are considered unimportant by

Voldemort.

Adapted from the script for Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 10: All’s Fair in War and Quidditch,

Copyright 2017-2018 by

Quantum Harry Productions and B.L. Purdom. See other posts on this blog for

direct links to all episodes of Quantum Harry.

Comments

Post a Comment