Essay: Horcruxes and King's Crosses

Part I of The Tarot Hallows essays:

Horcruxes and King’s Crosses

In

the last ten Quantum Harry essays I’ve been writing about each of the seven

columns in the grid of Tarot Major Arcana cards numbered one to twenty-one, with

three rows and seven columns (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 30: Harry and Tarot) aligning with each

of the seven books of the Harry Potter series, as well as the seven sets

of sequential cards (1-3, 4-6, 7-9, etc.) also aligning with each of the seven

books, in order. The last essay will actually be four essays, as this is the

blog version of the final episode of Quantum Harry, the Podcast, which

is an extra-long installment. This will be the first of four essays.

The seventh column, the

one aligned with Harry Potter and the Deathly

Hallows, has the Chariot (card #7) at the top, Temperance (card #14) in the

middle, and the World (card #21) at the bottom. In the first book of the series,

the Magician (#1) was the top column card and first sequential card. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 31: The Devil you Know and Episode 32: The Mirror and the Stone.) In the fourth book of the series, the column

and sequential cards intersect at Force or Strength (card #11), forming a cross.

(See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 37: The Goblet of Memory.) There is a final intersection: the sequential

cards for the seventh book, the last set of three in the cards numbered one to

twenty-one, are the Sun (card #19), Judgment (card #20), and the World (card #21).

All roads lead to the World card in this book, symbolizing wholeness, completion,

and home.

The

Chariot card being the ruling card for this book sheds new light on the

seemingly-endless travel in Deathly Hallows: it shows a figure who might

be a prince, king or magician using a wand, not reins, to drive a chariot with

dark and light draft-animals, sometimes shown as a black sphinx and a white

one, but often as a red horse and a blue horse. In addition to representing the

opposing forces shaping Harry, making him Liminal (see Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 8: Have You Tried Not Being Liminal?), these horses

can stand for Hermione and Ron, Harry’s best friends, who are opposites in some

ways but learn to “pull together.” He could not make the journey without them,

and when Ron is away for a little while, Harry and Hermione are nearly killed at

Bathilda Bagshot’s house in Godric’s Hollow. Red also happens to be Ron’s

emblematic color and blue is Hermione’s, while Harry’s is green, like his eyes

and the Killing Curse that repeatedly fails to kill him. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 7: Fountain of Youth.)

The

light and dark horses can also symbolize Harry’s journey to wholeness; he

cannot achieve this by ignoring his “dark side,” the Voldemort in him. He

carries a piece of his enemy; his understanding Voldemort helps him to succeed,

even as it sometimes frightens Ron and Hermione. The Chariot is another

archetype Harry embodies, a union of opposites, a Tarot version of the

archetype of the Liminal Being, as well as pointing to the extreme level of

travel in the seventh book. But in addition to symbolizing the archetypal

Liminal Being and travel, the Chariot may also be a link to the Horcruxes.

The word “Horcrux”

was coined by JK Rowling, and could have multiple origins. In a paper presented

at Phoenix Rising in New Orleans in 2007 (“Of Horcruxes, Arithmancy, Etymology and Egyptology: A Literary

Detective’s Guide to Patterns and Paradigms in Harry Potter”),

Hilary K. Justice suggests that one possible etymology combines hors, a

French root meaning “out of” or “outside of” with crux, meaning “essence,” as in “the crux of the matter.” This gives

us an object holding part of one’s “essence” (or soul) “outside of” the body.

I engaged in some etymological digging of my own

and found that the hor part of “Horcrux” is close to the hora, a

circle dance in Israel and Romania, which may relate to hor also being the Latin root for hour, pointing to another circular

image: a clockface. Crux means

“cross” in Latin, and combining a circle and cross results in a simple wheel with

four spokes (like the logo for Quantum Harry.)

This circle divided

into four quadrants has long been a symbol of the Earth, suggesting a compass

and the cardinal directions: north, south, east and west. It is the symbol used

for Earth by astronomers, including those at NASA, who prefer to say that the cross

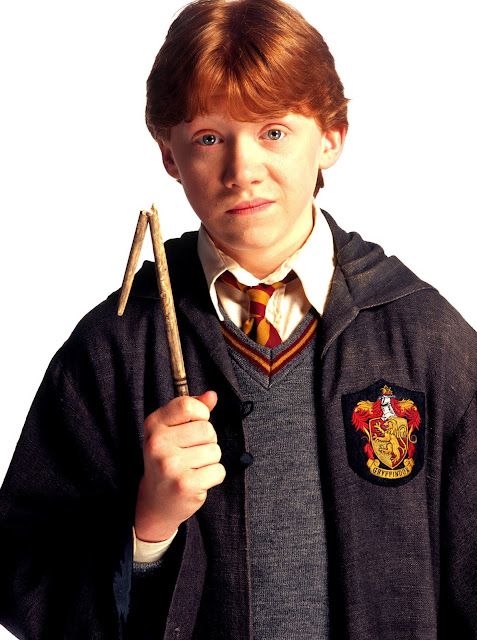

represents the equator and a meridian. This is also the shape of an ancient

race game that evolved into Pachisi,

Parcheesi and Ludo, among

others (it is also the format for an early Harry Potter trivia game,

pictured above). All of these games share the goal of reaching the center of

the cross, a center often called home,

which relates again to the Chariot card because this card is linked to the

astrological sign of Cancer, which is focused on issues related to the home.

This symbol is also reminiscent of medieval labyrinths, like the cross-and-circle

design of the labyrinth in Chartres Cathedral, seen in the photo below. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 18: The Wide World.)

Earth is the element

out of the four alchemists recognized—Fire, Air, Water and Earth—linked to

Voldemort, since his birth-sign, Capricorn, is an Earth-sign. Earth is also the

element of the Devil archetype, which Voldemort embodies, and in turn,

Capricorn is the astrological sign linked to the Devil card in the Tarot Major Arcana,

which depicts a rather goat-like Devil. (Capricorn means horned like a goat.)

In

another combination of opposites, the circle with an embedded cross was also

called a Sun Cross, Solar Cross or Solar Wheel; it is linked to prehistoric

cultures, particularly the Neolithic to the Bronze Age periods in Europe. Thus,

a wheel with four spokes can also be linked to the Sun card and therefore to

death, resurrection, and the phoenix. Voldemort’s wand, until almost the end of

his life, contains a feather from a phoenix, and the purpose of his making Horcruxes

is to make him like a phoenix, one

who cannot die.

For a symbol that could mean “Horcrux”—a circle

with a cross—to be equated with the Sun also fits with the locket Horcrux being

a symbolic sun, like the golden ball in the Grimm fairy tale of the Frog King.

(See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 28: The Grimm Campaign.) The locket happens to be the Horcrux aligning

with the fifth book, Order of the Phoenix, the one aligned with the

fifth column of Tarot Major Arcana cards, which has the Sun card at the bottom.

(See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 38: The Order of the Heretic.) Finally, this symbol is also called a “Chariot

Wheel” because of the Sun god’s chariot linking heaven and earth in the myths

of many ancient cultures, connecting this both to the ruling column card for the

book, the Chariot, and its first

sequential card, the Sun. This is another reason that the Tarot archetype of

the Chariot is the equivalent of the mythic archetype of the Liminal Being, one

who crosses thresholds and is an axis mundi, a link between worlds.

Thus two possible

etymologies for Horcrux may both be something Rowling intended: a

word meaning that a person’s essence is elsewhere, outside their body, and a

word combining circle and cross, pointing to the Earth, which

Voldemort hopes to rule over; the Chariot, a Tarot archetype embodied by both

Harry and Voldemort, as it is the Tarot equivalent of the Liminal Being; and the

Sun, which in turn is linked to the phoenix, once a source of Voldemort’s power,

and an entity he wishes to emulate by creating Horcruxes, so that, like the phoenix,

he will be impervious to death.

The card linked to

the Chariot (#7) is the Tower (#16, since 1 + 6 = 7). In Deathly Hallows,

the Lightning-Struck Tower, the title of the Half-Blood Prince chapter in

which Dumbledore dies, is least symbolic of all. Hogwarts is under attack; giants

are literally tearing down the walls. It is a cataclysm, a violent rupture in

the fabric of wizarding reality. However, we can see the Tower card as both

upright and inverted here, since Hermione

and Ron visit the Chamber of Secrets, the inverted Tower of the second book, to

retrieve basilisk fangs. (See Quantum Harry, Episode 33: The Inverted Tower of Secrets.)

Below the Chariot in

the seventh column of cards is Temperance (#14), which was also a sequence card

for the fifth book. The back-and-forth of the liquid between the vessels on

this card shows the mixing of water and wine; watering wine ‘tempers’ it, makes

it less potent, and wine makes water more

potent. It is another union of opposites, like the Chariot’s dark and light draft

animals, and, as such, it is also about balance. Voldemort, in contrast, would

eject all Muggleborns from the wizarding world, seeing no value in diversity.

He is clearly incomplete because he has repeatedly ripped his soul to make

Horcruxes, but also because he rejects both the Muggle part of himself and his link

to Harry; as a result, he can no longer send even misleading images to Harry’s mind,

as he did in Order of the Phoenix, because he recoiled in horror when he

was exposed to Harry’s prodigious power to love. This ability to bridge worlds

is the power Harry has that Voldemort does not, and is well summed-up by love.

Luna

is again the Angel Temperance, an archetypal Crone, when she helps Harry cope

with Dobby’s death, as she helped him cope with Sirius’s death in Order of

the Phoenix. However, Harry also embodies the Angel Temperance in Deathly

Hallows; the ‘third eye’ on this card links to his “seeing” through his

enemy’s eyes, an ability he integrates into his skill-set. Harry’s being a Pope

or High Priest (card #5) is linked to Temperance as well (#14, since 1 + 4 = 5).

He has been a holy man ever since he was a bishop in the life-sized chess game;

here he transcends worlds by seeing through the eyes of the Other (Voldemort)

and by dying and returning to life, an intercessor for the entire wizarding

world.

As Master of Death, Harry understands the cycle

of life, instinctively summoning the shades of his parents, godfather and Remus

Lupin with the Resurrection Stone, presenting himself to die because it is

necessary to save his world, to protect those he loves and those he doesn’t. Harry-the-Hero does not just die for people

he loves; his love protects everyone.

Harry, High Priest, Liminal Charioteer and Angel Temperance, refuses to run, as

Aberforth suggests; the Master of Death transcends life and death and bestows his grace on all.

The first sequential

card aligned with the seventh book in the series is the Sun (card #19), symbolizing

another integration of opposites—life and death, since the Sun daily dies and is

reborn, linking this to the dying-and-reborn phoenix. Harry dies and is

resurrected in this book, but a doppelganger for him, Neville, also evokes the

twin children seen on some versions of the card.

Neville could have

been the Prophecy Boy, and after Harry returns from death, he echoes Harry’s

actions in the second book by stating his faith in Dumbledore as Harry did, with

a cry of, “Dumbledore’s Army!” Instead of Fawkes bringing the Sorting Hat,

Voldemort summons the Hat, which he plans to destroy because he only wants

there to be Slytherins at Hogwarts in the future. He puts the Hat on Neville

and sets it on fire, a substitute for Fawkes, who was the symbolic fire of the

Holy Spirit on Harry’s head in the Chamber, evoking the story of Pentecost.

(See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 13: Deus ex Machina.) The Hat is described as looking like “a misshapen

bird,” again evoking Fawkes, a phoenix representing the Holy Spirit, instead of

a dove, another bird symbolizing the Holy Spirit, who appears when John the

Baptist baptizes Jesus. After this symbolic confirmation, Neville’s coming-of-age

ceremony, he breaks free of the curse binding him and slays Nagini, whose head

spins “high into the air”—imagery suggesting again a similarity to a ball, like

a Snitch, which all of the Horcruxes resemble in some way, large or small,

physically or symbolically. (See Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 29: The Horcrux and Hallows Game.)

The

cards linked to the Sun (#19) are the Magician (#1) and the Wheel (#10).

Throughout this book, the influence of the archetypal Magician, Dumbledore, is

keenly felt. His backstory’s extremes are given before the truth. First Rita

Skeeter gets her say in a vitriolic biography, then Elphias Doge gives his

version. The truth is worse than Doge’s hymn of praise and not as bad as Rita’s

smear job; Harry finally receives a complete picture of the man in whose

footsteps he has walked on the path to death from his brother, Aberforth.

The archetypal Magician dogs Harry’s footsteps

from the beginning, when he reads excerpts from Rita’s biography, and he is

with Harry at the end, at King’s Cross, which was always where he crossed a

boundary between the “real” and numinous worlds. Now he finds himself on the

platform in a misty afterlife where he speaks to Dumbledore (who may or may not

be just in his head).

Rowling’s choice of

King’s Cross for Harry’s brief afterlife could be another

circle-and-cross reference. A sovereign’s orb in Latin is globus cruciger, part of the British Crown jewels. A globe symbolizes

the earth, a 3-D circle, and the orb is topped by a cross, another union of

circle and cross, on an orb that could be called a King’s cross. This is

an alternate earth sign to the circle with the cross inside it and both are used

as Earth symbols by astronomers.

The lore surrounding

King’s Cross may offer clues as to why Harry goes there after his death. Where

the King’s Cross-St. Pancras Station sits today may have been the site of a crossing

for the Fleet River in Roman times, outside the Roman settlement of Londinium.

In Christian lore, dying is often spoken of as “crossing the river” (Jordan).

This may also have been the site of a battle between Queen Boadicea and Roman

invaders; legend has it that she is buried beneath Platform Nine in the station—rather

close Nine and Three-Quarters.

However,

the name “King’s Cross” didn’t arrive until the nineteenth century, when a

statue of King George IV was erected at the Battle Bridge crossroads. In

folklore, crossroads are places where the fabric of reality is “thinnest”,

where travelers may meet spirits and have paranormal experiences. It is a place

of liminality. In Greek myth, crossroads were associated with Hecate and

Hermes, both psychopomps, entities who accompanied spirits to the Realm

of the Dead. Food was left for Hecate at crossroads during the new moon; one of

her titles was “goddess of the crossroads,” and she was a goddess of witches

and magic as well. Combining this intersection of roads with the king’s statue

gave it the name King’s Cross, which persisted even after the statue was

pulled down.

After he dies, when Harry is at King’s Cross

with Dumbledore, who seems to serve as his psychopomp, it is clear that this is

a crossroads for Harry; he can choose to “go on”—which ghosts like Nearly

Headless Nick never did, so Nick has no idea what comes next—or go back (not as

a ghost). This place has always been a threshold, inherently liminal, where

Hogwarts students leave the mundane world and enter the world of magic (even if

they are from magical families). Thus it is the perfect place for Harry to make

his choice. Once again, nothing is carved in stone for Harry; his choices make

him who he is, in life and in death, and Harry, the liminal charioteer, chooses

to return to the world to save it.

Adapted from the script for Quantum Harry, the Podcast, Episode 40: The Tarot Hallows. Copyright 2019 by Quantum Harry Productions and B.L. Purdom. See other

posts on this blog for direct links to all episodes of Quantum Harry.

Comments

Post a Comment